Music

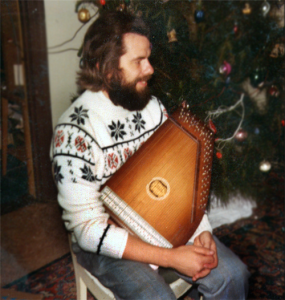

by Don Robertson (1983)

“This essay from 1983, never published, is from the frustrated 41-year old composer that I was at the time. Previously, in 1970, I had voluntarily left the culture of the mass mind to discover and bathe in the beauty and harmony of the great works of classical music. Here in this essay, I open and expose the wound that was inflicted on me by the world’s then-current cultural nightmare and offer the healing salve of the discoveries that I had been making during the previous decade. I have edited this article, adding footnotes to provide context and subtitles to separate the sections.”

Don Robertson (2022)

“How do you like that?” a friend said to me the other day as he turned up the volume on his car cassette-player. “That’s the Left-Brained Toadstool’s newest hit song!” [1]

“Great,” I replied, “it makes those rivet guns in that construction site across the street sound terrific!”

The fellow was not amused, but what could he expect me to say? I have not followed the music scene, via the radio and television, for many years. With a gesture of finality, I had turned my radio off in 1970 and it, along with the T.V. and Time Magazine, had gone sailing out of my door. I had had it with cultural garbage!

But now, twelve years later, I am as happy as a lark, no longer subjugated to the steady stream of radio-frequency energy demodulating into my eyes and ears… deadening my brain and lulling my sensibilities. But alas, I find myself a stranger in a strange land: a freak! No radio, no T.V., no E.T. products for my children! [2] Instead, I find greater joy listening to nature in the stillness of a mountain meadow, with the wind whistling lightly in the trees.

I am continually puzzled by the spectacle of a society capable of creating such wonders as our current technology nourishing itself on the kind of garbage that is fed them via that same technology. We have created the means to bring the highest quality of life and art to Earth, yet we insist on rolling in mire.

To talk with someone about music at this point seems to me almost absurd. I can’t imagine anyone listening to the “Good Friday Spell” from Wagner’s Parsifal while drinking canned cancer-inducers and eating glazed donuts.

The beauty and true meaning of music has become polluted. In today’s world, it provides that nice, quiet, easy-listening ambiance that mesmerizes us as we glide through the isles at the supermarket, and then assaults us from our car radio on the way home, with deadening, discordant sounds followed by voices, clearly from the lunatic fringe, assailing us with idiocy and fast-paced commercials. Yet we cling to our musical opinions as if they were such valued treasures.

“But classical music is well-supported,” my friend tells me, while we walk through the isles of our local one-stop record shop called “Record City.” He points to the small “classical” section in corner of the store. I look. (“What is the fare, here?” I wonder.) Ravel (“cheap and flashy,” I mutter), Copland (“trash”), Vivaldi’s Four Seasons (“third rate”), Mahler (“So what?”), Bernstein’s Mass (“Are you kidding?”), Pachelbel’s Canon (“Do you mean the ‘pop’ version with the added pizzicato cellos that everyone thinks is the original, or the slowed-down, out-of-tune ‘new-age’ version that puts you to sleep?” I wonder).

My friend persists: “All I have to do is turn the dial to our local classical FM station to hear the classical masterworks.” (“Do you mean the station that produces the steady stream of sleepy, obscure, baroque instrumental music all day… specifically programed to provide a pseudo-intellectual ‘background’ music?” I ponder).

Trying to explain music and art in a culture that takes punk rock and Arnold Schönberg seriously is like trying to sell air-conditioning to the Eskimos.

“But,” my friend would probably say, “music isn’t all that important anyway.”

Not important? Is music important? You only must ask yourself the following question: Has there been a time in your life when a very special piece of music had affected you very deeply? If so, was not that certain piece of music vitally important to you at that time? If your answer is “yes,” then you know that music can be important.

But then, what do Earth’s great minds have to say about the matter?

“Whoever has no knowledge of music knows other things to no purpose”

Seneca (c.4 BC – 65 AD)

“When I open my eyes, I find myself involuntarily sighing, because what I see around me is so against my religion. I must despise this world which does not understand how music is a higher revelation than all other wisdom or philosophy.”

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

“There is no higher truth obtainable by man than comes of music.”

Robert Browning (1812-1889)

“Music is a medicine for the soul. When a soul has lost its harmony, harmony, melody and rhythm assist in restoring it to order and concord.”

Plato

Plato did not feel that music should only create pleasurable sensations. He said that music should be used to develop character. He felt so strongly about the importance of music that he linked it with the welfare of entire cultures. According to the ancient Athenian statesman Aristides, the ancients ordered that music be a mandatory study to be pursued from childhood until late in life.

What was good for them should be good for us, but instead the prevalent music of the 1980s is the opposite from harmonious. From it, the ancients would have turned aghast. We have created a nightmare to reflect the monstrosity that we are creating simultaneously with our physical culture.

Gregorian Chant

At one time, music held together the spiritual fabric of the devout people of Europe whose everyday lives were imprisoned by the tight reins of the Roman church (its symbol, the dying Jesus on a cross, was adopted during the same time period that gave birth to the inquisition). The liturgical music of the Roman church, called Gregorian chant, was created before the advent of what is now considered to be the modern world. It consists of some of the greatest masterpieces of music in Western culture. Its emotional effect and great beauty are universally attested to, and few people are unmoved by it.

Gregorian chant arose from a synthesis of older Roman and Gallican liturgical chants during the 9th and 10th centuries. The finest examples that remain today were written before the 12th century.

There is a story about the power of Gregorian chant that I read about a few years ago. The article was about a Benedictine monetary in France that had been taken over by a new abbot who had modified life in the monastery according to the directives of the Second Vatican Council, also called Vatican II. This was an ecumenical council of the Roman church that during the period of 1962 to 1965, drew up the requirements that the pope of that time, Pope John XXIII, felt were needed to “update” the church, so that it might connect with 20th-century people in an increasingly secularized world.[1] The new abbot had eliminated the six to eight hours of chanting Gregorian chant per day by the monks. He claimed that chanting was useless, and that without it, the monks would reclaim six to eight useful hours every day.

As the days passed, the monks grew more and more tired. They called a meeting amongst themselves to determine why they had grown so tired and decided to lengthen their sleeping hours. But lengthening their sleeping hours made the monks even more tired, and so medical specialists were then called in. These specialists determined that the monks were suffering from starvation because of their vegetarian diets, and so meat was added to their meals. When this failed, Dr. Alfred Tomatis, a famous French otolaryngologist and inventor, who specialized in the ear and hearing, was called in. He found seventy of the ninety monks slumped in their cells “like dishrags.” The singing of Gregorian chant was immediately reinstituted. Five months later, in November of 1967, sixty-seven of the seventy monks had returned to their normal activities and to their legendary Benedictine work schedule.

[1] According to Cheney, David M. “Second Vatican Council”. Catholic-Hierarchy.org – Vatican II was record-breaking: “[Its features] are so extraordinary […] that they set the council apart from its predecessors almost as a different kind of entity,”

The Polyphonic Music Era

During the 10th century, parts of the Roman liturgy began to be expanded by adding one or more notes on top of the original plainsong melodies, thus creating the beginnings of what we call polyphonic music, where harmony is created by singing more than one note at a time. Polyphonic settings of the liturgy existed alongside the original plainsong Gregorian melodies through the centuries, until the changes of Vatican II that limited the use of Gregorian chant. Of the examples of early polyphonic music that have come down to us, the compositions of the 12th century French composers Léonin and Pérotin prove to be the most remarkable.

In the music of 15th-century composer Guillaume Dufay, the harmonic fusion of three melodies played at the same time flowered. The beauty of his music left a great mark on the evolution of Western music for centuries to come.

Dufay’s music is all but drowned out today. There are very few recordings of Dufay’s sacred liturgical works. The music is considered to be “too old” to be of any value other than to academics, who alone seem to know about it; but I have even spoken to some of them who deem the music to be of little aesthetic quality.

The 15th-century flourished with great liturgical polyphonic works. Flemish composers Jacob Obrecht and Johannes Ockeghem used mathematical formulae to weave melodies together in unheard of ways. Obrecht employed occult numerology and mystical symbolism to create his great works.

The music of Josquin des Prez spans the 15th and 16th centuries. He was a composer of first rate, like Beethoven and other more recognizable composers of later centuries, yet his music is rarely heard today. He was a magnificent melodist who could lift the soul like the wings of spirit. Some of his interweaving textures are in themselves masterpieces. Eighteen settings of the mass ordinary and about one hundred liturgical compositions – called motets – survive today.

Josquin’s later music stylistically formed the basis for the great Renaissance sacred music of the 16th century, where harmony flowered and many of the worlds’ great masterpieces of sacred music came into existence. This flowering reached fullness with the music of Flemish composer Orlando Lassus, Italian master composer Giovanni da Palestrina, and the great Tomás Luis de Victoria from Spain, whose music added a touch of angelic presence found nowhere else. Victoria, unlike other composers, wrote only sacred music. The beauty of this music is far beyond the ability of words to describe. The masterpieces from his pen are outpourings of spirit, of love and divine joy. Palestrina was a master musician whose work is of the purest celestial quality. Lassus’ outpouring contains rare heights of inspiration: music of the highest worth and beauty.

There are few words to express the magnificence and great worth of the extant liturgy of this era. Palestrina’s scores are, thankfully, available today in a very few specialty sheet music stores in major cities, but Victoria’s are out of print and only available in major university libraries, and only a third of Lassus’ total output was ever reprinted. Thanks to the great work of Carl Proske in the 19th century, whose labor was supported by King Ludwig I of Bavaria, many great masterpieces of the Renaissance were published in his great collection called Musica Divina. Reprints are available in some libraries.

Sadly, the editions that are available today in sheet music stores in the U.S.A. are a sorry lot. Latin words have been translated to strip them of their true meaning. In a few cases, the music has been carved up, with whole sections of a composition removed (who would dare remove sections from movements of Beethoven’s fifth symphony?). Modern editors, in order to secure copyrights for their publishers, distort the music with instructions and indications that were never included in the original music. And worse yet, known frauds continue to be published as authentic works. Because it appears in many hymnals, one of the best-known choral works with which people in America today associate the name of Palestrina is an Adoramus te Christe that was actually composed by Rosselli! Victoria’s famous four-part Ave Maria was definitely not composed by Victoria, as it has a completely different style than that of Victoria’s real works, and the composition Jesu Dulcis Memoria that is available in octavo-sized sheet music and ascribed to Victoria has been proven to be a misattribution.

Beginnings of The Instrumental Music Era

After the heights reached during the sixteenth century, musical style changed in the decades before the turn of the 17th century, when instruments began to take a more prominent role in the music of the church. The composers of the great Basilica di San Marco in Venice set the seeds for a new style of music, today known to the public by the term baroque. The new style began at the beginning of the 17th century, instigated by the Florentine Camarata in Naples.[1] This style of music, being more worldly, flourished in the theater as the first operas appeared. The music became even more worldly as the violin replaced the voice during the time of Vivaldi and Corelli. By the time of Handel, Mozart and Haydn, the great sacred works were composed for the concert hall, stripped of the plainsong that was employed in liturgical performance, and smothered in applause at their conclusion.

Johann Sebastian Bach was only a German church organist in his own time. Georg Philipp Telemann was considered to be the great composer of the era. Yet which work of Telemann can hold a candle next to the great oeuvre of Bach, whose music is so genuinely great that the only expression of their great beauty that man can produce is tears? Fortunately, the works of this great composer – whose sons helped form the concertos and symphonies of Mozart and Haydn and were famous in their time, unlike their father – were finally published in Germany during the 19th century… an undertaking that lasted a half of a century.

[1] The Florentine Camarata was the name taken by a circle of highly educated noblemen who regularly met during the last three decades of the sixteenth century. They believed that the style of classical music that was then current, the polyphonic choral style employed in Renaissance choral music, was not the kind of medium needed for drama, so they turned to monodic music instead, as it could metrically follow the words.

Richard Wagner’s Great Music Revolution

Beethoven, like Bach, needs no introduction here. He was a composer beyond composers… well, maybe except for Bach. Then along came Wagner, who carried on Beethoven’s great flame.

And now, I tread on the most controversial of turf: the subject of Wagner. The truth is that Richard Wagner is to the modern world what Bach was one-hundred years after Bach’s death: a mystery. Those who understand Wagner’s music belong to a universal underground fellowship. The true Wagner lies outside of the modern opera house. Wagner’s books and writings about music and theatre are far-advanced beyond the world of modern opera. Wagner cried against the kind of opera that dominated the stage of his day. His music dramas are not operas, nor were most of them intended to be.

With Wagner, European classical music reached its zenith. His music dramas are spiritual masterpieces. His music is exalted beyond description. Yet the kind of trash and lies that have been, and today continue to be, written about him are an example of the kind of resistance that only a society that worships the mediocre can create.

The only way one really understands Wagner is to become initiated. Once one becomes initiated, he or she usually will stay that way, although some – like Debussy and Nietzsche – reacted to their own near-worship with anger and rebellion. The name and music of Wagner stir the greatest anger and rebellion in many people. But sometimes they become initiated like did the conductor Leonard Bernstein, who believed that he detested Wagner’s music until one day, when he was required to conduct a Wagner composition and his emotion overtook him. He burst into tears on the podium.

The popular idea of Wagner, the great egotist who bleed his friends dry and covered up the truth with lies, is false. These ideas were purposely published to belittle Wagner. Even Brahms was not above this slander. He saw to it that Wagner was ridiculed in the press beyond the point where most anyone else would have been able to endure the slander. Wagner was attacked in the press and in publications unlike any other man. The impact of these lies is today so strong that few people know who Wagner really was or what his work was really all about. The most popular book of the 1970s in America was so distorted that it would shock any serious researcher. All of this is unfortunate, but the truth is that Wagner’s music is beyond the comprehension of most people.

Wagner not only changed the form of opera staging, presentation, and musical composition, but he influenced almost every composer who followed him and consequently the evolution of music itself. Wagner’s music drama Tristan und Isolde is considered by all major writers on the subject of music theory or history as the most decisive turning point in the evolution of musical style and harmonic structure since Beethoven. Those who scoff at the Valkyries and Rhein maidens today are laughing at the inspiration for the greatest literary movement in centuries, that which was begun in France with Verlaine, Rimbaud and Mallarmé. Wagner was the most important artistic influence in France during the second half of the 19th century, the spawning ground for the great French impressionist art movement, the important music of César Franck, and symbolist poetry.

After 1900, music began deteriorating, as a new kind of classical music began appearing. The focus of this new music was the Viennese composer Arnold Schönberg, who boldly created discordant music that shocked European audiences. His proclamation that the traditional music system, based on the laws of nature, could be superseded by his method of composition with twelve tones, a purely intellectual concept invented by Schönberg himself and accepted unequivocally by the academic community of the mid-twentieth century. Today, Schönberg is heralded as the great giant of 20th-century music.

Thanks to Schönberg, we have the music that growls in the background of violent movies and television programs: the discordant music that helps create the negative emotional state needed to properly appreciate the bloody slaughter and cold-blooded hatred of the horror genre that passes as “entertainment” today but is really only a modern canned version of the Circus Maximus of ancient Roman times.

The music scene of today is one where the true value of music is unknown. While Christo drapes islands in saran wrap[1], the beat pounds on and the punkers[2] assault us with absurdities, the world’s resources are pillaged and waisted and its peoples grow less and less educated and more and more subdued (nice word for brainwashed by the forces of the media and the military-industrial complex). Meanwhile, in the midst of this madness, we have California’s latest cultural phenomenon: the New Age (TA-DAH!).

[1] In May 1983, the “artist” called Christo created a “modern art project” by surrounding islands in Biscayne Bay, Florida with six-and-one-half-million square feet of floating pink woven polypropylene fabric covering the surface of the water and extending outward two-hundred feet.

[2] Punk rock was a music genre that emerged during the mid-1970s.

“The New Age”

The idea that a fully blossoming new age can naturally coexist with the kind of turmoil and decadence that defines today’s World is absurd. It’s kind of a Nero-fiddling-while-Rome-burns situation, where the people participate in the most disgusting “Brave New World” of sex, drugs and rock and roll, or whatever pleasure “gets them off” the most, while down the street in a commune of micro-dosed new-age “hippies,” the new-age of light and beauty has already begun. Insensitive to what is going on around them, they live in a false ambiance of technological security. Clearly, if there is to be a new age, it has not yet arrived. Instead, what masquerades as a new age are the modern-day temple-merchants of pleasure-loving California, who sell us the new age in the form of records, cassettes, seminars, books, clothes, food, pills ad infinitum.

I am not trying to say that I am against everything that is called “new age.” I was one of the first to create a new-age record album in 1969. What I am saying is that there cannot be a fully developed new age coexisting with its opposite. “New age” is a term that is being used more and more here in California, but it is just another marketing ploy to separate man from his money. Instead of helping people find themselves, and their brothers, and their planet, this “new age” is only another variation on the same old theme: pleasure and self-titillation. Bland, emotionless, spacey new-age music may offer an alternative to the frantic decadence of today’s lifestyles, and people who have become tired of the discords and noise may find relief in these soft sounds, but I believe that the threat of ambient background music outweighs by far its beneficial aspects.

Muzak

Great music must be listened to, not turned down and played in the background. It is in the background that the distinction between great music and mediocre music becomes blurred. Background music is “muzak” and new-age background music is just new-age muzak, which for me conjures visions of a brave-new-world of people living in a technologically induced fantasy, while the real world is dying around them. [1]

Concerning background music, by the way, the Muzak Corporation was the expert, and in the studies that they conducted in factories during the 1930s, playing canned music to factory workers, the found that background music that was played continually during working hours had a destructive effect on the factory workers performance and state of mind, and that only a few hours of it at a time had provided any beneficial effects at all. This was also supported by experiments that have been conducted with plants.

[1] Muzak is an American brand of background music played in retail stores and other public establishments. The name has been in use since 1934. (Wikipedia)

Music in the Twilight of the Gods: The Computer Musical Instrument

I feel that there has been only one major revolution in music in the 20th-century, and one only, and that is technology. You can forget the so-called achievements of the 20th-century composers that those who make their money by selling books try to shove down our throats. I believe that the 20th century has produced little great music. Technology is the only great revolution that has occurred in music, and we are all experiencing it now: Electronic Music (now rapidly becoming “computer Music”).

Did you realize that chances are that “electronic music” is already your favorite kind of music?

My definition of electronic music is: “Anything that comes out of a speaker, and that you call music.” According to my definition, you probably have been listening to, and enjoying, electronic music for quite some time, but you didn’t realize that it was electronic music because that was a term that we were told applied only to musical experiments with Moog synthesizers and such. The television set and the tape deck have evolved to the point of becoming necessities for many modern people. During the 1950s, the electronic music produced in recording studios was usually reproducible in a live concert venue, now it is usually not. What music do we listen to that is not somehow electronically amplified, even in concert performances? Without microphones and electric guitars, would we today have “Kiss”? [1]

The computer will become man’s greatest musical instrument. With it, mankind can be redeemed or sacrificed. That is a powerful statement, but only reflect upon the power that electronic music wields over us now: very few people live without it. Many knowledgeable minds have gone into the creation of today’s electronic music, and it forms in one way or another, the very fabric of our lives: in the supermarkets, drugstores, from radios everywhere… It sells us toothpaste (while we watch an overly large amount being spread on a toothbrush), it makes the lonely man cry, the happy man sad, it creates rebellion, or it creates fusion. Some people have grown so addicted to it that it accompanies every moment of their lives, creating a “safe” and familiar background. And now that we have entered the new arena of computer music, computer music looks to become the basis of our national musical lives. But man’s greatest instrument is only as good as man’s greatest inspiration, or man’s greatest striving. In the hands of the artist, it can help realized his greatest aspiration, yet in the hands of the businessman, it can become the means for the elimination of the artist himself, which would spell the final blow, and the downfall of music itself.

I am truly sorry if I have spoiled someone’s day because they have read this article in anticipation of something more positive and entertaining, but let the chips fall where they may. All I can say about the problems facing our World is, if you are not a part of the solution, then you are a part of the problem.

[1] Kiss (stylized as KIϟϟ) was an American rock band formed in New York City in 1973. (Wikipedia)