Classical Music in the

21st Century

by Don Robertson (2000)

Classical Music in Retrospect

When we talk about the classical music that was composed in Europe, Great Britain and Russia through the 19th Century, we must understand that this was a style of music that was supported by the ruling classes. For example, in the 16th Century, it was the music of the church (during the same century, India’s classical music was created in the courts of the great emperors).

During the early part of the 17th Century, after the influence of the reformation had begun to spread throughout Europe, a new kind of classical music arose in Italy: a secular entertainment music that was not associated with the church. It was during this period that the first operas were composed in Naples.

Classical music, whether sacred or secular, has singular characteristics that differentiate it from the music of the folk, or the common people.[1] These are some of the characteristics:

- Classical music is usually highly structured.

- The structure and creation of classical music is analyzed, then taught to preserve its tradition. It becomes a part of our institutions of higher learning.

- Classical music is performed by musicians who have been trained for many years in the genre.

- Classical compositions are often longer than the tunes of folk and popular music, but not always.

- Classical music is considered to be a form of art akin to classical painting, sculpture and literature.[2] Classical art is usually differentiated from ‘folk art,’ but it is not necessarily better than folk art.

[1] It must be remembered that in past times, there was a distinction made between common people and nobility and royalty. It is interesting to note that what we refer to as popular, or pop, music is really a form of folk music. While classical musicians are trained carefully, learning the essentials of the music as these essentials have evolved through tradition, pop musicians – just like folk musicians in any part of the world – spring up spontaneously. As far as conception goes, there is really very little difference between the birth of a jazz band in a brothel in New Orleans or the birth of a rock and roll band in a garage and the birth of a folk ensemble in an Irish village. These are all movements that have begun spontaneously, indigenously, as an expression of the people… the folk.

[2] Most classical art has a refinement that removes it from the level of the streets and places it in the salons, where it is appreciated by people who are usually educated and refined. Classical art is found in painting, sculpture, literature and music. Just as there are many people who have not yet discovered the joys of great poetry or great painting, many of these same people have not really listened to or found joy in the great compositions of the classical music literature. One of the benefits of art is its ability to raise the understanding, feelings and consciousness.

Twentieth-Century Classical Music

During the 20th Century, contemporary classical music was considered to be part of a long and evolving tradition. But the association of the music with the royal courts and the ruling classes had disappeared. By the middle of the 20th century, classical music was available to anyone who owned a television set or radio. However, the tradition was still associated with people who had a certain breading or refinement (hence the term ‘high-brow music’).

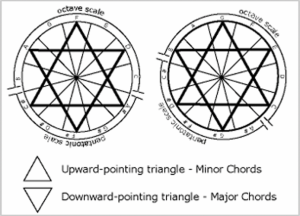

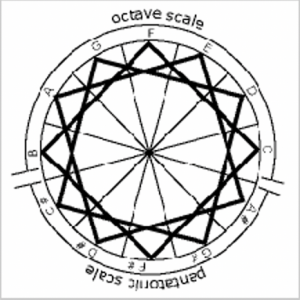

As the tradition of classical music evolved in Europe during the 20th Century, it left behind its former elements of romanticism that represented the style of the 19th Century and instead embraced the doctrines of Viennese composer Arnold Schönberg who introduced what was called atonality and serialism. As I have explained in other articles, these new elements introduced negativity into music.[1] During the 19th Century, classical music had expressed emotions such as joy, sadness, grief, love, passion, and hope. This music was anchored to the traditional seven-note scale, or octave, that had been employed in all music since long before the birth of Christ. Pythagoras demonstrated that this seven-note scale was a natural phenomenon and not an invention of mankind. The foundation of music is established by the octave and major and minor triads: the three-note major and minor chords that are used in all music.

Schönberg introduced the concept of atonal music in his compositions early in the 20th Century. This atonal (meaning non-tonal) music was not based on major and minor chords. Schönberg‘s early atonal music created near riots at concert performances.[2] In the 1920s, Schönberg had begun using a method of “composition using twelve-tones” that became known as serial music composition. Using this method, all twelve notes of the chromatic scale are treated equally.[3] Since Schönberg’s new style of music no longer differentiated between consonant and discordant musical intervals, Schönberg allowed the door to discordance to be opened, and thus he broke the underpinnings of traditional music, underpinnings that had been based on natural laws. Schönberg composed a dark negative music that influenced many composers throughout the 20th century, and he became the composer who caused the greatest change to the tradition of western classical music during the last century.

The style of classical music that was prevalent during the third quarter of the 20th Century was inspired primarily by Schönberg’s student Anton Webern, whose completely intellectual music can create a disjoint and confused emotional state in the listener.[4]

During the 1960s, the music and ideas of American composer John Cage had become an important influence. Cage brought classical music to the point of being little more than noise. Here we have music that was governed by chance, where the rolling of dice determined what notes were to be used in a composition. Cage’s ideas are indeed very interesting, and they certainly gave composers an impression of freedom from the servitude of tradition and law along with a feeling of freshness and originality. But the universe is based on order, not on anarchy and chaos, as Cage’s theories might lead one to imagine. In truth, Cage’s music is to Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony as Christo’s Wrapped Trees is to Michelangelo’s David.

[1] You could say that Wagner was perhaps the first to introduce negative elements into classical music when he used the musical interval of the tritone to represent negative influences in the music drama Siegfried.

[2] Apologists for the music of Schönberg usually like to say that all new innovations in classical music have always created similar riots. This simply not true. Naturally, a music filled with discordance was an abhorrence to the concert goers of the early 20th century. It took many years for people to get used to this kind of music, mostly thanks to television and the motion picture industry who use negative music to give emotional impact to violence, suspense and horror.

[3] The chromatic scale consists of the twelve notes of the octave: the seven white keys of the piano, plus the five black keys.

[4] I have long been condemned for my views on the music of Schönberg and his students Webern and Berg and the ensuing art music of the 20th century by individuals who love this music and listen to it all of the time. All that I can say is that “I have been there, done that, and it is time to move on.”

"Morty"

I began to recognize the reality of the state of Western classical art music in 1967 while I was attending the Julliard School of Music in New York City and studying privately with the late composer Morton Feldman. During the 1950s, Morty, as he was known to his friends and students, was a member of John Cage’s circle, but by the time that I knew him, he had already broken with Cage. Morty composed a different kind of music and had a completely different aesthetic.

Every Saturday morning, I took the Lenox Avenue subway to Morty’s upstairs apartment in New York City to study with him. We sat at the large grand piano in his front room surrounded by large abstract paintings by his friends Franz Kline, Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollack. I would bring the composition that I was currently working on, and note by note, Morty would go through my music and make suggestions and comments, explaining how he created his famous chords and note combinations.

My music at that time was completely under the influence of Anton Webern, but I was daily becoming more influenced by the music of Christian Wolfe, another member of the Cage group, and Morty himself. The one record that I owned of a Christian Wolfe piece was a musical composition that was very sparse with a lot of space between the notes. I used to listen to this record not at its intended 33 1/3 RPM speed but at the slower 16RPM, which created even more space and sparsity of notes. Meanwhile, Morty was introducing me to his own world of ‘quiet sounds’ and he spent many hours showing me how he created his chordal combinations, stressing the value of ‘each sound, each note.’

However, while I studied with Morty, I was also studying with the great master of North Indian classical music, Ustad Ali Akbar Khan. Khansahib, as his students called him, had recently arrived in the United States and was teaching five or six students in his New York apartment. I found myself learning two different types of music at the same time. I went to Khansahib to learn the deeply spiritual ancient music of India, strongly based on the foundations of natural scales, and to Morty to work on music that was based on discords.

By 1968, my compositional technique had evolved to the point of total rejection of any consonant musical intervals.[1] My music by this time was based on the two most discordant intervals in the scale: the tritone and the interval of the minor second.[2] I had to work very hard when I composed to try to get these intervals to influence the sound of the music and to minimize hidden consonant intervals.

At first Morty had a difficult time accepting the direction where I was heading. He used the tritone and minor second intervals all the time in his music, but he used consonant intervals such as the minor and major third when he felt they were appropriate, and so did other contemporary composers such as Stockhausen and Boulez. To me, these had now become mistakes. For Morty, my music was too sparse, and it lacked something.

But one day, he turned to me and said, “You have passed beyond John Cage and myself. And that is only natural, since you are a part of the next generation.”

Once he had acknowledged what I was doing, I decided to write an important composition in my new style. Morty helped me in my selection of instruments. This piece would be for bass clarinet, trumpet, celeste, guitar, violin, bass, and percussion. I worked on it for a year.

As the year unfolded, I grew more and more frustrated writing this composition — that I later named Last Piece — because of the difficulty that I had in restricting the consonant intervals. I could hear what I wanted in my mind, but creating the music was an intellectual challenge because of the consonant relationships between intervals that could develop between notes that were separated by other notes. I used to tell Morty that what I really needed was a computer to help me compose this music, but computers were not a commodity in 1968.

As I struggled with the creation of my Last Piece, I also reflected upon the great difference between the music that I was creating with Morty, and the music that I was playing with Khansahib.

[1] A musical interval is determined by the distance between notes.

[2] The tritone is the note that divides the octave in half (i.e., the interval C-F#). It was called the devil’s interval during the Middle Ages and the renaissance and was avoided at all costs. The minor second is the smallest interval of the scale. If you play the notes E and F together at the same time, that is a minor second.

The Duochord

One day I was reading a book by Corinne Heline about music and its spiritual effects, when I noticed that there was a diagram in the book that explained how the twelve notes of the musical chromatic scale corresponded with the twelve signs of the astrological zodiac. At that time, I was interested in astrology, not in the modern use, but as it was used in ancient times, and I thought this was an interesting concept. The way she explained it, the notes were placed counterclockwise on the circle of the zodiac as follows: C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C#, D#, F#, G#, A#. She had learned this from Max Heindel, a Danish American Christian occultist, astrologer, and mystic. It was the 7-note major scale (the white keys of the keyboard), followed by the 5-note pentatonic scale (the black keys of the keyboard): the two most powerful scales in music.

I was fascinated by this discovery. Astrology is based on a circle, around which are drawn the 12 astrological signs. Positive and negative relationships in astrology are determined by where one sign stands in relationship to another. I began to wonder that if this was the case in astrology, wasn’t it also the case for the twelve notes of the musical chromatic scale (the chromatic scale in music includes all the black and white keys of an octave).[1]

With this in mind, I drew astrological trines in a circle that had Corinne Heline’s note values assigned to it. In Astrology, the trines, or triangles, define the most positive relationships between the signs: harmony and concord. To my surprise, applying the trines to my drawing not only yielded the most positive relationships between the signs, but also the most positive relationships between musical notes: the major and minor triads. The four triangles created two major triads and two minor triads on the circle! This showed me that by assigning the notes to the circle as she had described, the overlaying of triangles yielded the very foundational elements of music itself: the major and minor triad!

[1] I am not talking about the newspaper variety of astrology, but the very ancient astrology that was an integral part of astronomy.

After marveling at this for a while, it came to me to draw squares. In astrology, squares represent the negative elements: discord and lack of harmony. So, I drew the three possible squares. I looked at what ensued and was completely shocked! There before my eyes I saw the very chords that were the foundation of the music that I had been composing. Each square was a four-note chord made up of two half tones separated by a tritone.

Whether you believe in astrology or not is unimportant. Here we are dealing with mathematics and symbolism. They are important because they give insights into the inner workings of nature. And I realized that I was looking at a mathematical representation of the very conflict that I was beginning to feel emotionally in my life: the music that I was composing with Morty on one hand, and the music that I was playing with Khansahib on the other. One was based on the triangles, the other on the squares. With Morty, I was composing music that was completely negative!

That realization bothered me a great deal, and I contemplated it for months. I loved my duochordal music, and if what I was beginning to understand was indeed true, I would have to abandon it, because I knew in my heart that I did not want to create something that was negative.

Finally, I decided to speak with Morty. I told him that I had a conflict developing within me. He listened carefully as I asked him: “Do you think that this music that you and I write is…,” I stumbled for a tasteful word to use, “…unnatural?”

He answered me immediately, without any reflection, and his answer surprised me. He said: “Yes, it is unnatural, but if you ever quote me on that, I will deny that I ever said it.”

I realized that this was to be our last lesson. The two years of weekly visits would be over. I was sad, but I knew it had to be.

That summer, I moved away from New York, following Khansahib to the San Francisco area where he was establishing a school for North Indian classical music. In San Francisco, I recorded my album, Dawn. This was the album that reflected my struggle between the two shades of music, light and dark…a struggle that would soon be played out on my last battlefield. After the album was completed, my wife and I left San Francisco for a six-month stay in Mexico and Guatemala. There I would perhaps find my way, purify myself, and maybe find a true spiritual path.

For months I struggled within because there was still a part of me that had a strong desire to write duochordal music. But one night, in a dream, I heard a duochord composition being played that consisted of a succession of one negative chord constructed of disharmonious intervals succeeded by another, then another, and so on. The music was being played very loudly by a very powerful brass ensemble! Every time one of the loud chords sounded, it sent a cold shiver up my back, and I felt a wave of darkness flow over me. I awoke in a state of panic and terrifying fear. I knew at once that I had to completely let go of my desire to compose and enjoy duochordal music. But it took nearly a half a year south of the border to free me from the grip of negative music.

A Change of Direction

After months in a tiny thatched-roof hut on a beautiful, deserted beach west of Progresso in the state of Yucatan, Mexico, I felt purified. I now had a new direction to follow in music: a positive direction. I knew now that John Cage had performed the final straw for classical music: he had brought it to a state of noise! I had read in a book by Peter Yates about 20th Century music that “Music is born out of the ordering of noise.” I was now ready to start anew.

In 1970, in my book called Kosmon, I wrote a series of articles about music. In this book I explained the concept of the duochord, the state of both pop and classical music, and introduced my ideas on the relationship of music and mathematics. I also wrote an article about various musical and social influences, including negative music, and how they fit into the cyclic duration of a society. At the end of the duochord article, I made this bold prediction about the coming changes in rock music:

“The Chinese called it indecent music. During times of great negative influence, such as ours, this indecent music appears. So, what is it? Are we talking about the sleepy banality of muzak, that piped-in office music and middle-of-the-road FM fare, or the speedy, nervous energy of jazz, or the hardcore dissonance of so-called “contemporary music” played in concert halls and in movie houses and on our television sets (providing background for violence and horror flicks), or a super-hostile electronically amplified music–the culmination of all the above–that may manifest itself in all its horrors during the 1970s?”

Aware of the changes that would occur musically during the coming decade, I gave away my radios and my TV set in 1970. I turned instead to the discovery, research, and enjoyment of positive music, beginning with the great ancient traditions in Western classical music: Gregorian chant and the music of Victoria, Bach, Palestrina, Lassus, Josquin, Dufay and Gallus. As I studied each composer’s music and each musical period, I purposely looked for music that was truly positive, glorious and uplifting. By 1976, I had worked my way forward in time to the music of Wagner, César Franck and Alexander Scriabin…music from the late 19th Century.

Realizations

During the last half of the 1980s, after my intense study of classical music styles from Gregorian chant through romanticism, I realized that one of the problems facing the art of classical music was that a false expectation of stylistic improvement was always present, just as it was also expected in the art of painting and the other arts, that in any time-continuum, as art evolved, it must also evolve stylistically by incorporating newly discovered elements, and that the older styles would become archaic and should be left behind. There was always a historical precedence for this: new discoveries always brought about a stylistic change in art, and this change created the next step in the evolution of that art form. Monteverdi and the composers of the early 17th Century introduced radical changes into the music of his time, and thus the music evolved to the style of the baroque era that reached its zenith in the music of J.S. Bach.

Bach’s sons contributed to the beginnings of the style of the classical era, and they greatly influenced both Haydn and Mozart, who brought classical-era music to its zenith. Beethoven and Schubert altered the state of classical music with their new discoveries and were the first great masters of the romantic era, culminating in the late 19th Century with the music of Richard Wagner. Schönberg introduced atonality and changed the course of classical music in the 20th Century, then along came John Cage and the music of chaos. From chaos is born the cycle of music again, but this time we have a full cycle of music behind us, plus the ability to learn of the traditions of music in other parts of the world, including the great countries of India and China, with their highly developed classical music traditions that we have not had the ability or the desire to explore before.

After realizing that there was always an expectation for a stylistic improvement to further art music along, and that older styles were considered archaic for no concrete reason, I realized that during the 1980s, this ‘improvement’ had become a style known as minimalism.[1]

I believe that it is time to abandon this concept of stylistic improvement as the criteria for which a piece of music is accepted or not. It is this false sense of improvement that continually gives birth to the avant guard and other superficial and degenerate artistic movements that imply a rejection of the past. It is fine to make new artistic discoveries, as we have seen in the past, but what is important to realize is that at this time in history, the beginning of the 21st Century, we have taken art through an entire cycle, and now instead of looking to the style of art for the answer to what is acceptable in music, we need to judge art by different criteria. We had become slaves to style! We had to dress according to the most current style, our homes and our furniture, they had to be chic, and we had become victims of trends in eating, in smoking, trends in art, trends in music. We were a society of sheep blindly following some preconceived notion of what had value and what did not. Awakening to our own inner potential and the realities of the universe that we live in is critical!

This realization completely freed me from the boundaries of what I now considered a false evolution of art music. I had brought an end to atonality in my music by discovering the composition of music using duochords, the root of negative music. This was the same end to which I felt the negative classical music of the 20th century was unconsciously evolving. With my new freedom, it was not necessary to embrace yet another ‘improvement.’ The whole concept of artistic evolution through creating a new style and abandoning previous styles, I now realized was contrived and not necessarily real. Evolution in music did not represent a step-by-step ‘improvement’ in style, but instead dealt more with the evolution of man and our understanding of ourselves, our environment, each other, and the true meaning of art itself.

Thus freed, I realized that as a classical musician, I was able to write that which best represented the state of my soul and my feelings using any of the techniques that I wished to use, be they new, or of past ages, or even techniques that I had learned in my studies of non-Western classical music, or from what I had learned in jazz, rock and roll, or in blues. In fact, this is what many classical composers were already experimenting with during the first half of the 20th century, before the total embracing of atonality and serialism…composers such as Stravinsky (neo-classicism), Bartok (folk music), Ives (marching bands), Messian (bird song, Indian scales), and Milhaud (Jazz).

[1] Minimalism was a term coined to describe a style of music that evolved out of a composition made by Terry Riley in the late 1960s called “in C.” Riley’s music had significance at the time because he was a classical composer that had rejected atonality. The stylistic features of his work were imitated by others and a new style of music, later termed minimalism, was born. Composers who fit into the minimalist category include Phillip Glass, Steve Reich and John Adams.

What's Ahead?

Now that the 21st Century is upon us, it is necessary to examine our concepts and behaviors and attempt to understand why we are even using such historical terms as jazz, classical, new age, and county to classify our music when it has become so obvious that the crossover between these styles grows day by day. In fact, we have become caught up in our sub-categorization of sub-categories: I fully imagine terms such as “retro-ethnofusionary techno-rap” and “neo-industrial ambient gospel music” becoming terms that some marketing type would likely dream up.

Instead, it is time to look at music as music, and judge it by its merits, usefulness, and emotional quality.

We need an art music that will contribute to the evolution of mankind: something that is advanced enough to provide the emotional nourishment for the people of this new century. After all, this is what took place in each of the past five centuries. The 16th Century gave us our treasured renaissance sacred music, the 17th Century gave us magnificent baroque music, the 18th Century gave us the classical-era music of Mozart and Haydn, the 19th Century gave us those amazing romantic compositions, and the 20th Century gave us negative music!

I believe the emotional tone of 21st Century classical music should be one of spiritual unfoldment: music that has a positive influence, that stimulates those areas in the human psyche that are uplifting and pure, that give comfort, hope, and feelings of spiritual unfoldment; the opposite of the feelings invoked by the negative and intellectual classical music of the 20th century. And we need to reexamine the now-ingrained ideas we teach to the younger generations about the music of the last century: ideas that have been unconsciously propagated by each generation such as “Igor Stravinsky, the World’s Greatest Composer!” Baloney. Stravinsky was a selfish, irritable old man who sat in his Hollywood home writing unbearably ugly distortions of music on his horribly out-of-tune piano.

When I talk about spiritual unfoldment, I am talking about a process that has nothing at all to do with religions that were invented by man and end up serving those who seek power. Not that there isn’t truth in religion, and not that one cannot have a spiritual experience in a church, masque, or temple. The supreme being, intelligence, consciousness, spirit… whatever you wish to call it… is, after all, everywhere. In places of genuine worship, this supernormal presence can be amazingly strong. But religions, in addition to the good they serve, also help keep us divided, and that is not the way of the spirit, that divine presence.

I talk about unfoldment as an experience that I understand, as do others. And only those who have had genuine spiritual experiences can grasp what this means. The world’s great music is a product of a spiritual anointing. That’s the way it works. Paul McCartney understood that when the song “Yesterday” came to him in a dream. Some Christians in the South of the United States, where I currently reside, will take issue with that song having anything to do with spirituality, but it did, and it remains an important step in human evolution, like it or not. I have been in churches with these same Christians and I experienced tremendous movements of spirit, as have they, and I have experienced tremendous healings. It’s all there, always… and always in different dress. Stravinsky may talk about his spirituality, but those who understand the spirit, no matter how little of it they comprehend, would recognize that it just isn’t present in the religious music that he wrote during those final years in Hollywood.

Music must resonate with this spirit, spiritual energy, or whatever you want to call it. And to do so, it must resonate with the harmonic overtones of our creation. This is the most important thing that I can say, my most important message. This is the most difficult thing for so many musicians to grasp. When we were led away from the consonances, the major and minor triads, the thirds and sixths of music… the pure overtones of sound… by men such as Stravinsky, Schönberg and Cage, and by Jimi Hendrix and Jimmy Page in the “rock” world, we departed from the light, accepting the darkness instead.

In the meantime, the art of classical music lost ground. It became amorphous, undefined, unaccented, and unimportant. Polluted by years of abuse, the abuses of the Cages and the Schönbergs, it slipped into meaninglessness and dilettantism. Then it was preempted in our high schools by rap, which is largely simple beat and rhyme. How crazy it is that so many people send their children to schools where they learn nothing of the arts, the only subjects that will provide real inner stability and harmony.

I have stood alone in what I have been saying for thirty years, with only a few individuals standing beside me. I have been called everything in the book, yet I continue to speak, because I know that what I am saying is the truth, and I know that I am here to speak this truth, and that gradually this truth will radiate out into the world to the extent that it will help create a change.

For in this 21st century, we no longer will require a music that expresses the stress and frustration of the 20th Century. Its music was a product of electricity being harnessed, of machinery, of bombs and petrol fumes. These became constant irritants. We were fixated on war, on pain, on separation, on hatred. Look at what we have created for ourselves to watch on our miracle called television! I don’t have to spell it out.

Why do we need to return to consonance and to the music of composers who, like those of older times, resonate on a higher level? Because all those stress-inducing influences (prognosticated by Anton Webern near the beginning of the 20th Century in his Six Pieces for Orchestra) are still here, and there are even more to come.

The music of the 20th century was a necessary step in our evolution. Now that we know what negative music is, and once we realize what positive music really is, we will be able to achieve a balance.