Vincent d'Indy - Tableaux de voyage

by Don Robertson (2005)

© 2005 Musikproduktion Höflich, Munich Germany

This is the article that I wrote for Musikproduktion Höflich for

the introduction to the score for Vincent d’Indy’s symphonic composition “Tableaux de Voyage.”

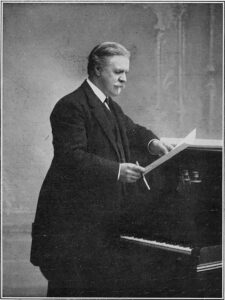

Vincent d’Indy (1851-1931) was a French composer and teacher. He was a co-founder of the Schola Cantorum de Paris and also taught at the Paris Conservatoire. His students included Albéric Magnard, Albert Roussel, Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud, and Erik Satie, as well as Cole Porter. D’Indy studied under composer César Franck and was strongly influenced by Franck’s admiration for German music. At a time when nationalist feelings were high in both countries (circa the Franco-Prussian War of 1871), this brought Franck into conflict with other musicians who wished to separate French music from German influence. (Wikipedia)

Vincent d'Indy and the Transition to Modernism

An amazing era in classical music took place during the 19th century. The first performance of Beethoven’s revolutionary third symphony, the Eroica, on April 7, 1805 was the signal that an era of romantic music had begun. Masterworks will flow from the pens of many composers: Schumann, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Brahms, Dvorak, Tchaikovsky, Wagner, Franck and Bruckner, among them. The era continued through the century, its end finally arriving with Arnold Schönberg’s romantic masterpiece Gurreleider, composed from 1900 to 1903. This huge orchestral and choral composition sounded the death knell for the romantic era as Schönberg will lead the way from light to darkness, abandoning the universal principals of harmony and the overtone series in his pursuit of what he considered to be the next evolution in music.

While many composers followed Schönberg on the road to discordant harmonies and atonality, some did not. Among the detractors was the French composer and educator Vincent d’Indy. According to Andrew Thomson, in his book Vincent d’Indy and His World, d’Indy called Schönberg “a madman who teaches nothing except that you should write everything that comes into your head… His work… is no more than a mass of meaningless notes.” On another occasion, d’Indy’s student, the composer Arthur Honegger, suggested to d’Indy that Schoenberg’s music was to be read, rather than to be heard, to which d’Indy replied: “These noises don’t interest me on paper any more than they do in the atmosphere.” He had no sympathy for discordant music. He considered “modernist” Edgard Varese, who was a student at d’Indy’s Schola Cantorum, a dishonor to the teaching of the school.

D'Indy's Background

Vincent d’Indy (1851-1931), was born and raised in Paris. In 1872, he enrolled in César Franck’s organ class at the Paris Conservatoire, and soon Franck, who taught a group of young French composers in his home, became d’Indy’s mentor and composition teacher.

D’Indy’s musical interests distanced him from the formal instruction that was being served at the Conservatoire, and in 1896, in conjunction with Charles Bordes and Félix-Alexandre Guilmant, he founded a new music school, the Schola Cantorum, becoming its first director. The mission of the Schola was to forge a return to the tradition of Gregorian chant and music in the style of Palestrina, with new music inspired by these traditions, and to reform the system of music education then in place in French schools. D’Indy wrote a complete course of composition that started with Gregorian chant and continued historically through to the music of the composers of his time, as d’Indy was in complete support of both Debussy and Ravel. D’Indy remained the director of the Schola Cantorum until his death in 1931. The Schola remains today a highly regarded institution.

Photos of the Scola Cantorum in Paris, France

(photos by Don Robertson – 2007)

D’Indy’s Legacy

D’Indy has left us with an awesome legacy of music: sonatas, piano and organ works, symphonies, operas, orchestra works, chamber and choral works. Additionally, he wrote articles about music, and books about Franck, Beethoven and Wagner. He had a passion for studying and performing the great composers of the past as he, like Brahms, learned from and supported the music of the masters that proceeded him. He wrote piano transcriptions and orchestral revisions for works by the French baroque composers Jean-Philippe Rameau and André-Cardinal Destouches, the Norwegian composer Johan Svendsen, and his friends DuParc and Chausson. His modern transcriptions of two great Monteverdi operas, Le Couronnement de Poppée and Orfeo, are still in general use today. Among the students who benefited from his teaching were Joseph Canteloube, Erik Satie, René de Castera, Albert Roussel, Marcel Labey, Guy de Lioncourt, Déodat de Séverac, Isaac Albeniz, Joaquin Nin, Carlo Boller, Henri Gagnebin, Arthur Honegger, and Darius Milhaud.

Emmanuel Chabrier is at the piano.

From left to right: Adolphe Julien (critic), Boisseau (violinist at the opera), Camille Benoit (art historian), Edmond Maitre (érudit), Lascoux (magistrat), Vincent d’Indy, A. Bigeon (romancier et critique)

This painting is in the Musé d’Orsay in Paris

Tableaux de voyage

The beautiful symphonic composition Tableaux de voyage is a fine example of Vincent d’Indy’s genius and also a wonderful example of his use of the cyclic technique (l’unite cyclique dans l’oeuvre d’art) that he so greatly expounded during his lifetime and in his Cours de Composition Musicale. It is a technique that incorporates harmonic, rhythmic, and melodic material from different movements, allowing works of music to become more unified. D’Indy traces the cyclic technique to Beethoven, but it was first fully developed and expounded by his teacher, César Franck.

Tableaux de voyage was a result of a trip that d’Indy had made to Bayreuth in August 1888 to hear Wagner’s Meistersinger and Parsifal. D’Indy realized his impressions of this trip as a set of thirteen piano pieces: Tableaux de voyage Op. 33, Treize pièces pour piano that Leduc published during the following year. Subsequently he orchestrated six of the thirteen pieces, and these were published by Leduc in 1891 as Tableaux de Voyage Op. 36, suite d’orchestre en 6 parties. The work was first performed on 17 January, 1892 at Havre, then soon after at Angers.

Tableaux de voyage - Piano Version

Tableaux de voyage - Orchestra Version

Rather than describe only the six pieces contained in the orchestral score, I will present all thirteen pieces because they form a whole, even though d’Indy, for one reason or another, did not orchestrate all of them.

1 – Préamble – D’Indy designated the first of the thirteen piano pieces simply as “?” (a question mark). The name was changed to Préamble in the orchestral score, however. The time signature for Préamble is 5/8, a very rare occurrence in 19th Century music. The piece begins with a six-bar introduction employing four chords: C minor and Ab minor played twice: a harmonic motive that will reoccur later. Following the four-chord introduction, what d’Indy refers to as the Préamble theme is announced by clarinet, followed by a variation, a middle section, then a repetition of the seven-note theme. This time, however even though the 5/8 time signature is preserved, the melody is actually in 4/8. A motive, based on the Préamble theme, will have its way throughout the course of Tableaux de Voyage.

2 – En marche (Walking), is a stunning programmatic musical portrait. D’Indy may have conceived of this delightful tune while walking through the alpine hinterlands. Listening to this finely orchestrated piece one can perhaps visualize d’Indy’s adventure. In the sixth measure from the end, d’Indy reintroduces the so-called Préamble motive (the first five notes of the theme from the first piece) in half-notes (F, Ab, Cb, C, F), carefully making note of this in the original piano score, apparently to help show the pianist the way in which he reuses melodies. The F note in this case is on the tonic (in the first movement the corresponding note was the major third).

3 – Pâturage (Pasture) is the first of the seven pieces that were not included in the orchestral version of Tableaux. I will briefly describe these to give the reader a better understanding of the whole work. Marked “doux,” (soft) Pâturage is an idyllic piece in ¾ time using a melody that creates a contrasting hemiola feel of 3/2 time.

4 – Lac vert – (Green Lake) describes a serene lakeside view most likely inspired by beautiful Lac Vert close to the franco-swiss border, high in the Alps near Mont Blanc. Lac vert appears in the orchestral set, following the next piece, Le glas, but it is the other way around in the piano version.

5 – Le glas (The bell’s knell). A new melody is presented in two periods, then d’Indy brings back material from the Préamble). At measure 17 we discover the four-chord introduction reorchestrated and now in the key of G#. The first and third chord contains no third; parallel fifths in the base keep a consistency with those used in the first period of the theme. The four-chord motive is followed by the first four notes of the Préamble motive similarly harmonized using fifths. The Le glas theme is then again presented in two periods, followed by a coda based on the four-chord motive.

6 – La poste (Mail coach). Here, d’Indy paints a picture of one of the ubiquitous mail coaches employed in Europe during his time. Postilions (who guided the horses that were drawing the coach) used a small brass horn to signal the arrival the mail. Use of the horn was obligatory for the postilion, who had to know at least eight signals, each with a particular meaning. The post horn was in constant use in Europe for several centuries.

The remaining pieces in the set, with exception of Rêve, the final piece, were not orchestrated. We will speak of them briefly.

7 – Fete de village (Village festival) is a lively waltz-tempo piece that incorporates the Préamble motive into the end of each of the piece’s two sections.

8 – Halte, au soir (Resting place in the evening) is a short piece in 4/4 time.

9 – Départ matinal (Morning departure) is an animated piece in 3/4 time. Written in ternary form, the middle section is a new presentation of the Préamble melody, not just a four- or five-note motive, but the entire melody, but in ¾ (6/8) this time (instead of 5/8). D’Indy concludes this piece with a coda based on a combination of the Préamble theme and one of the motives from the main section of the piece.

10 – Lermoos is a small rustic Austrian village overlooked by the Zugspitze. Marked “plutôt lent,” (somewhat slowly) this lovely piece was inspired by d’Indy’s visit to this beautiful location. The middle section is based on the Préamble theme.

11 – Beuron. To capture the spirit of this German town, d’Indy composed a Bach-like chromatic fugue, or at least the beginnings of one. The first four notes contain three notes of the Préamble theme, another overall unifying factor in the cyclic technique. Following the exposition is an episode built on melodic sequences, then there follows a freeform counterpuntal section that presents the melody of the fugue along with two counter melodies, one of them being the B.A.C.H. (Bb, A, C, B) motive that the master himself employed in Die Kunst Der Fuge. D’Indy carefully indicates in the piano score the four places where he employs this motive.

12 – La pluie (Rain) is a somewhat impressionistic sound painting of a beautiful scene with falling rain.

13 – Rêve (Dream). With this piece we return to the orchestral version, as this is the last piece in both it and the set of piano pieces. D’Indy has now returned to his home and reflects upon his now completed journey. Rêve is based on remembrances of the places that he experienced. It begins with the C min/Ab minor chords from the first four bars of the first Préamble piece, bringing us full circle. From this Rêve flows into an expressive string setting that is suggestive of a dreaming state, and perhaps loosely based on the Préamble motive. This is followed by a short segment of music taken from Le Glas with the original slow melody now played quickly with staccato notes. The music drifts back into the dreaming melody again followed by a section based on Lac Vert, then the dreamy music again, this time orchestrated with woodwinds, horn and pizzicato strings instead of the lush string orchestration of before. Finally, we have a reiteration of the full Préamble theme in 5/8 as presented at the very beginning of the the Préamble, followed by a coda based on the dreamy material, and a quote of the Préamble motive prominently played by the low strings. The piece then comes to an end.

Wonderful music, I look forward to its inevitable discovery and return to the concert halls.