Dawn: The Making of an Album

by Don Robertson (2001)

As I write this, thirty-two years have passed since the release of my first album Dawn.There has been a lot of interest in the album and I get inquiries about it frequently. A number of people have asked me for background information. With this in mind, I have prepared this essay. The story begins in New York City, where I was studying music and working as a studio musician.

The Contract

The major record label Mercury Records called me one day in 1968 and told me that they would like to sign me as a recording artist for their subsidiary Limelight label, originally a jazz label headed by Quincy Jones. There had been 48 jazz albums released on Limelight between 1964 and 1967. After that, the label was transformed from jazz to releasing music by avant-garde artists. The first album that was issued following this change of direction was by the French composer of Musique concrète, Pierre Henry. Albums of avant-garde and cutting-edge music that included everything from electronic composers and atonal jazz musicians to sitar players from India will be released after that. Mercury also told me that Abe “Voco” Kesh had listened to my guitar work on an album called Neon Princess by Tom Parrott and wanted to be my producer. Abe, who was also a San Francisco disk jockey, had just finished producing several albums with guitarist Harvey Mandel, who had a single called “Christo Redentor“ that was being frequently played on the radio at that time.

I had already decided to move to San Francisco to continue my North Indian classical music studies with Ustad Ali Akbar Khan. As soon as the contract with Mercury was signed, I was on my way.

The Conception

My wife Suzy and I were pretty deep into the “hippie” lifestyle at this point of our lives, and it was easy for us to give away and pawn almost all of our wordly belongings, including wedding presents that we had received only a little over two years before. We loaded up our 1965 Mustang with what we wanted to keep and departed on our drive across the country.

We arrived in California sometime in the spring of 1969 and set up a tent on Mount Diablo in the East Bay, and there we lived for a number of weeks. Following this, we moved into the front room of my sister’s one-bedroom apartment in San Francisco, sleeping on the floor. This was called crashing in those days.

I drove to San Anselmo to meet with my new producer Abe Kesh, and I liked him right away. He pulled out all of his favorite jazz records and played me various cuts, while he explained that what he had done for Harvey Mandel, he could do for me, creating a hit single and a great best-selling album, along with introducing me to the music world as a leading guitar player. He told me that he was close friends with the great West-Coast jazz musician Shorty Rogers, and that Shorty would bring in his entire band to back up my guitar work.

It was a great opportunity, but I had other plans. I told him I had something different in mind, and off I went, on my own, to work on what I was going to do.

I was at an interesting juncture in my life. In New York, I had been studying discordant “contemporary classical music” privately with composer Morton Feldman and – along with a half dozen other students – with the great master from India, Ustad Ali Akbar Khan. At the time of the offer from Mercury, I had been rehearsing with an avant-garde rock group that I had formed called The Don Robertson Trio. I was supposed to record an album for MGM. However, when my producer at that time, Alan Lorber, heard the music that I was creating with the group – the first known example of death metal music – he was furious, telling me that he never wanted to see or hear me again. The song that we played for him was completely angry and discordant, and 1968 was a bit early for that.

The goal of The Don Robertson Trio was to present music from the full spectrum that ranged from full-on evil to highest and most uplifting, the later being music like what I had been learning from Ustad Ali Akbar Khan. We even had an instrumental version of one of the songs that had been sung by the great Egyptian singer Umm Kulthum.

I had realized from my experiments and research during my two-year hiatus in New York City that there was a distinct difference between the music that I was studying with Ali Akbar Khan: the ancient and spiritual art of North Indian classical music; and the music that I was writing while studying with Morton Feldman: music based on discord. The difference was that Indian music was positive, the other negative. The Indian music had a tremendous spiritual quality, but the discordant music did not.

I felt that my feelings about negative music had been substantiated when I discovered the existence of a four-note chord that I soon dubbed the duochord. This discovery, although lost on most everyone around me, was significant for me. In fact, it changed my life. I realized that I did not want to create negative music anymore, and I would have to completely wean myself from it.

Now that I had the opportunity to create an album, I had to choose. I could create an album of positive music only, but I wanted to express all that I had learned about positive and negative music. My producer was willing to let me do what I wanted, and so I decided that I was going to create an album that would present my amazing discovery of the duochord with a demonstration of positive and negative music. One side of the album would be devoted to positive music, the other to negative. I decided to call the album Dawn, a play on my first name and a reference to the “dawning of a new age”, as in the song the Age of Aquarius.

In New York, I had been listening a recording imported from India of Raga Darbari Kanada performed by the Ali Brothers. In fact this record had become a part of my life. One of the singers in this recording played an instrument called the swarlamangala that appeared to me to be the same instrument as the zither instruments that I had seen Manny’s Music Store in downtown New York City. I bought an 85-string zither from Manny and tuned it to the natural pentatonic (five-note) scale, the most harmonious scale that exists. I began improvising on this instrument, using technique that I had originally developed with the guitar.

The music that I was producing with my zither tuned to this most harmonious scale was extremely powerful and uplifting. I decided that it would be the cornerstone of my new album. I thought about filling the entire first side with a single solo performance on the zither but soon decided that I wanted to feature some other aspects of the positive music that I had been working on.

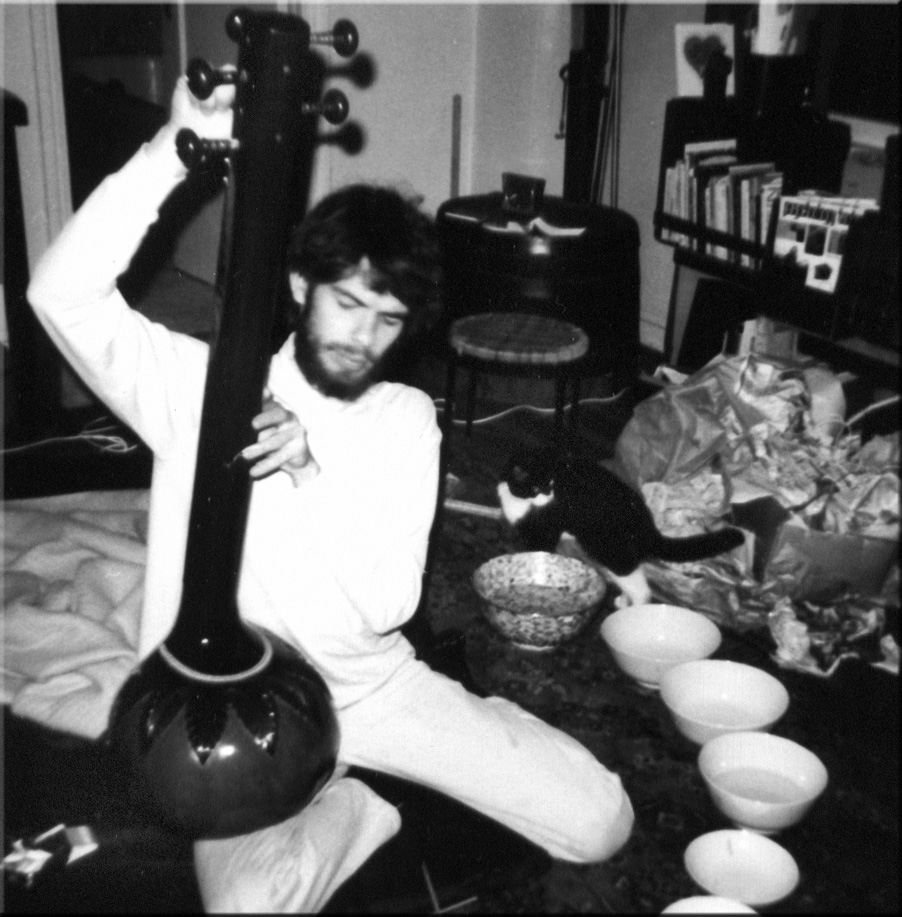

I decided that I would attempt to play Raga Darbari Kanada myself on the guitar, and that I would also create a pentatonic piece using a Jal tarang, an Indian instrument that consists of a set of tuned bowls.

When you strike the edge of a china bowl, it produces a tone. The pitch of this tone can be altered by adding water to the bowl. If you arrange a set of bowls in a circle and tune them with water, you can play this set of bowls with a suitable object (I used chopsticks).

Suzy and I visited San Fransisco’s Chinatown, where we carefully selected a set of bowls that would meet our needs. The sales attendants in the stores stood back watching us curiously as we pulled bowls of various sizes from the store’s shelves and tapped them, holding them to our ears.

For the negative side of the album, I decided that I would pull out all of the stops on the kind of music that I had been experimenting with in New York with The Don Robertson Trio: completely atonal and violently loud cacophony. I would also create a piece of electronic music that would feature the duochord.

The drummer from The Don Robertson Trio, Mike Dahlgren, had followed the hippie movement to San Francisco and was now living there. He was the consummate hippie. In New York City, he and his “old lady” had been living in a broken down room in the East Village, where the walls were covered with scribblings and writings that they had made on their numerous acid trips. “I am certifiably insane,” he would brag with a grin on his face, throwing back his long locks of hair. With this ploy, he was able to receive welfare checks every few weeks, and these provided him with his living expenses.

I would use him on my album. I had an affinity with him because we both loved to play in unusual meters such as 5, 9, 11, and 13. I knew no other rock drummer who could do that.

Getting Ready

Mercury had just opened an office in San Francisco and was building a studio on the ground floor. Since the studio was not yet finished, Abe scheduled some time at Columbus Recorders with legendary recording engineer George Horn. There, we would begin recording the new album. As we got closer to the recording dates, I worked with George, arranging for the rental of the various instruments that I wanted to use: a celesta, a glockenspiel, a set of orchestral chimes, among others. A Hammond organ and a piano were already available in the studio.

Mike Dahlgren’s friend Marcia would provide a flute solo that I wanted on the duochord piece. Another fellow named Rand Elias would play bass on the negative piece, and an electric violinist that we had met and liked was going to play on the album also. I can’t remember his name, but he told us that he had been playing with the San Francisco group called It’s A Beautiful Day.

Rehearsing the Negative Music

I wanted to rehearse the negative piece and Rand found a place where we could do it. It was some kind of club that was closed one night a week. We all met there on the next closed evening and set up our instruments. I explained to the musicians what I had in mind. I told them that we would be creating an extremely negative form of music. The bass player, the violinist, and I would need to turn our amplifiers up as high as they could go, detune our instruments, and then start playing the most horrible sounds we could conceive of, creating a piece of music that would be the most terrifying, angry, and hostel that anyone could imagine.

Rand and Mike were ready, but the violinist looked pretty puzzled. I was hoping that we would not have any problems because usually when I played this music in New York, it blew out the speaker in my guitar amplifier.

As we started playing, Mike began working himself into a frenzy and the little club quickly became filled with our terrifyingly hostile wall of sound. Soon, the violin player, with a look of complete disgust on his face, packed up his instrument and walked out. Not long after that, the owner of the club told us to leave. But it was OK. I had demonstrated to Rand and Mike what I had in mind, and they were doing their job well. We were ready for the recording.

Columbus Recorders

When the first recording session took place at Columbus Recorders, Mike and I sat down to record our first piece: my rendition of Raga Darbari Kanada that I ended up calling “Contemplation“. I knew that I really didn’t know how to play this raga (and I really didn’t), but I wanted to at least capture what I could of it, using my electric guitar. This raga is very difficult to perform correctly and there was no way that I could actually play it with the little training that I had at that time. Mike and I decided to use a rhythm of five beats divided as 2 + 3 and repeated over and over at a rather rapid clip. This created a kind of two-beat feeling, the second beat being a little longer than the first.

Next, we recorded the zither piece that I called “Dawn”. We followed that by tuning the jaltarang and creating the piece called “The Candle“. Then, I created “Belief” using piano, celesta, chimes, and glockenspiel to create duochordal music blended with various sound effects. I chose these instruments because I wanted to soften the effect of the duochords. “Belief” is a sound collage, something that I had been doing quite a lot of in New York. Finally I created three little short pieces that I would use to tie the others together. These were called “What?”, “Where?”, and “Why?”.

Pacific High Studios

We did not have enough time to record the negative piece at Columbus Recorders, and so Abe moved us over to Pacific High Recording with the legendary engineer Dan Healy. Rand, Mike and I set up our instruments for the negative piece while Dan, Abe, and my sister sat in the control booth not knowing what to expect.

When we got the high sign to start, with guitar and bass amplifiers cranked to full volume, we proceeded to unlock the gates of hell. We played twenty minutes of ear-splitting, hideous music. As this unfolded, Mike worked himself into an emotional frenzy, bashing his drums with his heavy drumsticks and powerful hands. Finally, my guitar amplifier blew out completely and Mike, now worked up into a serious state of rage, kicked his drums all over the studio, smashing the heads with his feet. Then, waving his two broken drum sticks over his head, he stormed out of the studio. The negative piece for Side Two had now been completed, and it was exactly as I had wanted it.

I walked back to the control booth to find the people inside drained, shocked, and embarrassed. Abe’s friend, the legendary KSAN disk jockey Dusty Street, had come in during the performance. She now sat, covering her face in her arms on the counter in front of her. Abe had a surprised look on his face, and Dan just looked the other way. Suddenly, Mike burst in, his face decorated with a triumphant grin. He was completely naked!

That night, Rand, the bass player, sat down to talk to me. With a serious expression, he told me that I should reconsider using the negative piece that we created that day for my album. It was the old question about art: was I expressing something, or was I just simply creating it? I knew the music that I had created was evil, and my conscience was bothering me already. He told me, “If you release that piece of music, it may cause the final San Francisco earthquake!” He looked at me with a deadly serious stare. We were both stoned on grass, and in my stoned state of mind, it all made sense. I started feeling a sense of responsibility and wondered if the music that I had just created was perhaps more powerfully evil than any that had been created before.

I gave Rand’s advice a lot of consideration. I respected him at that time, as he was the one who had introduced me to the teachings of G. I. Gurdjieff, from which I had greatly benefited. Even if the earthquake part was a bit extreme, I wondered if I should be responsible for unleashing this kind of music on mankind. After all, I was trying to create an album that expressed what the difference between positive and negative music was, and I had already realized that I needed to disassociate myself from negative music. And so, instead putting the entire negative piece on the album, I decided to use only a few glimpses of it, just enough to give a quick view of hell on earth, then quickly contrast these with snatches of the “Dawn” piece that I had recorded with the zither. This would present a back-to-back comparison.

Amigo Studios

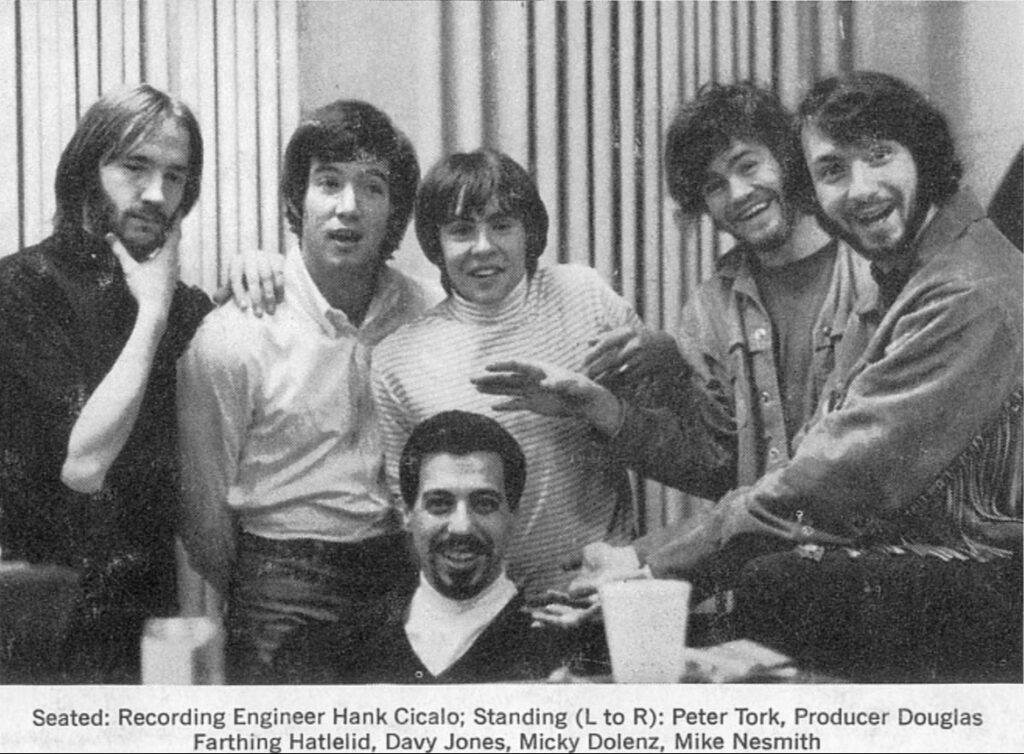

The final mixing and editing of the album took place at Amigo Studios in the Los Angeles area. The engineer was the legendary Hank Cicalo. He and I hit it off right away. I explained to him exactly what I had in mind, and that it would involve lots of editing, which in those days meant cutting and splicing tape. I explained the kind of stereo panning that I wanted, and how I wished to bring together the various elements of the duochord piece that I had decided to call “Belief“. Hank was just the kind of guy to get involved with this crazy San Francisco hippie and his Electronic-Webern-Indian-Rock Opus.

Hank told me that he had won two awards for the work that he had don on the Monkee’s first two albums. “The Monkees never sang nor played on either of these albums,” he explained to me. “The first time that I saw them was after the second album had been finished.”

Hank and I had a great time editing. Soon, we had lengths of tape draped all over the control room as he cut and spliced. I had sections of tape that I wanted to play backwards, mixing in with other sections that required special panning and stereo effects. Shorty Rogers came in to watch. He liked what we were doing, he said. I knew that I was going completely outside of the standard boundaries of music.

The Album

The resultant album, Dawn, was my epistle to the difference between positive and negative music. It was also a tribute to the dawning of a new age, where the consciousness of mankind would be raised to a greater understanding of spiritual unity and an attunement with God.

The album’s first side contained the exposition of positive music. It opened with a recitation by Suzy of the opening sentences of the Hindu holy book, the Isha Upanishad, while my piece of harmonious zither music called “Dawn” unfolded. To perform the piece, I tuned the zither to the natural pentatonic scale (C,D,E,G,A – the most harmonious of all scales), creating a powerful, spiritual music. Ten years later, when I was performing in concerts in the San Francisco area, dozens of people were transformed by the music that I played on the zither. They would line up afterwards to tell me this, speaking sincerely, obviously affected by the music (which also left me in an amazing spiritual state). However, others complained. They felt that the music was too aggressive. They wanted me to play tinkley fairy-dust music, like that they had heard in incense-laden metaphysical book stores. My music just wasn’t like that.

The next cut on the album was the short transition piece called “Why?” I had planned that the album would be continuous, with all of the pieces tying directly into each other, without pauses between them, but whoever did the mastering of the tapes after they left Amigo Studios did not follow Hank Cicalo’s instructions. Therefore, on the LP, there are spaces between each cut.

The next selection was called “Contemplation”, the piece that I described above. Mike crafted a steady five beats to the bar while I created an unfolding, sustained melody with the guitar. This piece was followed by another short transition piece called “Where?”, then the final cut for Side One, “The Candle”.

“The Candle” contained a recitation by Suzy and Marcia taken from the Chinese book I Ching. While Suzy and Marcia spoke of “the darkening of the light”, the jaltarang played the scale from Raga Malkauns in the background. This recitation was a lead-in to Side Two, the negative side that followed.

As I had decided not to include the long negative piece that I had created at Pacific High Studios, I needed a replacement. I had asked George Horn, the engineer at Columbus Recorders, to keep the mic open to record random moments while Mike and I were in the studio. He had recorded about ten minutes of Mike playing the steel drum while I hammered away on the tabla, a piece of music that I had never liked. Since it had a disturbing effect, I used it to build up to a place where “When?” would begin and where I would introduce a short snippet of the negative piece followed by a snippet from the “Dawn” piece, back to the negative piece again, followed by the voice of Mike explaining that “I see the entities before me now…,” comments that George had caught with his open mic while Mike was talking about the sounds produced by the glockenspiel that I had asked to be brought in.

The remainder of Side Two was occupied by the composition called “Belief”. This piece opened with Marcia playing a short melody on the flute. It then moved into sounds of tug boats in New York Harbor while I played duochords in the background. From there, the piece moved into a sound tapestry that ended on a major chord with an ominous chime note the key that was a minor-second higher.

The Cover

The cover art for the Dawn album is a story in itself. I spent a lot of time contemplating it. When approached by Mercury as to what I had in mind, I told them that I wanted no writing at all on the front cover. “Dawn by Don Robertson” would simply appear on the spine of the album. Mercury would have nothing to do with that. They insisted that my name and the album title appear blazingly on the top of the front cover “so it could be seen in record display racks in the super markets” (as if that would ever happen!).

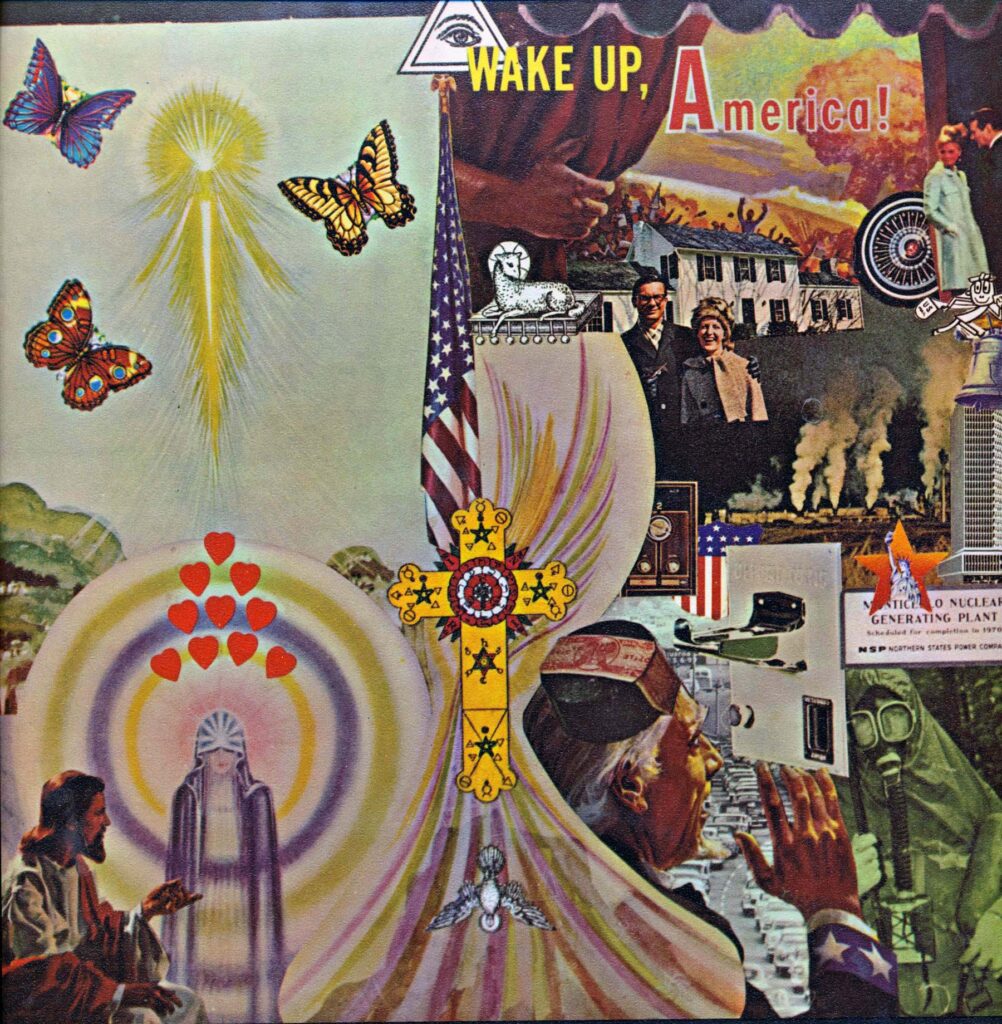

Next, I submitted the art that I wanted on the front and back cover. The front cover was a collage piece that I had found in a little store on Haight Street, near the corner of Asbury Street. The back cover would be a collage that I made myself. Mercury turned down the collage for the front cover, but surprisingly, they accepted my collage for the back.

My collage was called Wake Up America!. I had put it together late one night in my sister’s apartment. I felt that it explained the concept that I was trying to communicate with the music in the album. The collage was separated into two sections separated in the middle by an American flag, a hermetic cross, and a descending dove. The cross is an ancient symbol used by the Rosicrucian Brotherhood, and the descending dove is a symbol representing the descent of the Holy Spirit from God to man.

On the left there was a heavenly scene with a picture of an angelic being, the Master Jesus, and some sort of apparition in the sky. These all came from various books that I had been reading at the time. Using stickers, I added three butterflies to the sky (representing the eternal trinity: positive, negative, and the All) and ten hearts (representing the decapod of Pythagoras).

On the right, I had assembled a collage that represented what I considered to be the horrors that man was creating on Earth because of our non-acceptance of the spiritual world. These were an “Uncle Sam” with a liquor cap on his head, a traffic-congested freeway, a man fully suited in protective clothing in the process of spaying deadly pesticides, a coin slot from a Coca-Cola dispensing machine, a sign from a nuclear generating plant, a tall glass-faced air-conditioned building, factories belching toxic fumes into the atmosphere, a TV channel selector switch, the liberty bell, Mr. Zip (the symbol for the Post Office that represented to me the ability of advertising to shape our opinions), a young yuppie couple (they weren’t called yuppies then, however), a rubber tire, a nice suburban home, a symbol representing the seals in the Book of Revelation, and a hand that is drawing back a curtain to reveal a holocaust with the words “Wake Up, America!”. The latter I had taken from a bible tract that I had found carefully tucked underneath my windshield-wiper blade one day while shopping.

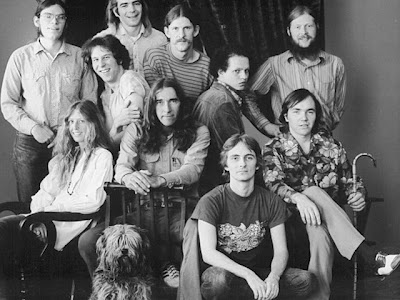

Since Mercury had rejected my original cover proposal, they sent in a photographer who was to do a photo shoot. I suggested that we drive to Mount Tamalpais across the bay in Marin County. There, we posed for various typical album-like shots. None of this was working for me, however. Finally, I struck on an idea. The first floor of the building where Mercury had its offices in San Francisco was under construction, and there was a big pile of construction scraps, beer cans, and other rubbish there. I told the astonished photographer to load his camera with black and white film and meet me in the construction area. When he arrived, I escorted him over to the trash pile where I had carefully placed my Fender jaguar guitar to make it appear as if it were part of the collected trash. I then sat on top of the heap and lit up a joint. This was all dutifully recorded by the photographer in black and white. Now I had part of my album cover.

I carefully instructed the art department at Mercury as to what I wanted. They were to find a magnificent color photograph of a beautiful Hawaiian sunrise. Next they were to cut out the background from the black and white photo of me on the pile of rubbish, then crop in the color photo of the sunrise as the new background. It would be an amazing cover of me smoking a joint while I sat on a pile of rubbish that included my guitar, all in black in white, with a magnificent sunrise in full color in the background.

South of the Border

Now that the album was finished, Suzy and I left for Mexico. With the money that we had made from the album, we hung out in Yucatan for most of the rest of the year, finally ending up in Belize and Guatemala. My object was to cleanse myself of all the negative music that I had been involved with and hopefully to discover some spiritual reality. When I finally received a copy of the completed album and saw what Mercury had eventually created as the album cover, I was shocked and dismayed. They had superimposed someone’s idea of a terrible-looking orange sunrise sideways on top of my black and white photo and printed my name in hideous orange and red colors on the top of the album. It was awful. But there was little I could do about it from my hammock swinging between two tropical trees that bent gently in the soft summer breezes on the shores of the beautiful Gulf of Mexico!

While we were living on the beach near Progresso, Yucatan, I read In Search of the Miraculous, a book about the teachings of Gurdjieff. It was my reading companion for the six months that I lived in Mexico and Central America. Difficult to understand, but full of truths, I studied this book in detail, cross referencing the various parts to gain the whole picture.

It was in Progresso, in the Yucatan, that I met a wild-eyed hippie named Wendel. He and his “old lady” (a stunning blond beauty who wore no underwear under her loose-fitting dresses) were from Laguna Beach, California. He had a thick, neatly trimmed mustache and always wore an ear-to-ear grin that I assumed he got from too much LSD. He wanted to build a club in Progresso where he would fill the dance floor with laser beams and strobe lights. His eyes glowed like light bulbs when he talked about this vision. It would be a place of spiritual transcendence! He had driven to Yucatan from California in an old Volkswagen, and he had an eight-track player in his car that seemed like a miracle at the time. One day he turned me onto the group called the Moody Blues. “The Moody Blues are where it’s at!” he told me matter-of-factly. We slipped into his car and I listened in amazement to this newly found joy, a rock group from England.

I immediately fell in love with this music. The group had only a few albums out at that time, but they were magnificent! The Moody Blues sang with transcendent harmonies and never produced a discord. The words to their songs were about the spiritual truths that I had been studying.

The Aftermath

After I returned to San Francisco from Mexico, I played the Dawn album for various people. My magical question was “Which side do you like the best?” The answer was always “Side Two”. I did not tell them that was the negative side. I realized that no one got what I was saying about positive music. I began telling everyone that it would take thirty years for people to understand the album.*

The construction work at Mercury’s studios had been completed, and I went there to create some of the music that I was going to use on my second album, specified in my contract. Fully inspired by the Moody Blues, I wanted to make a positive rock album.

I began by auditioning musicians so that I could form a band. Mike Dahlgren would be my drummer again, but Rand was now a sad mess, completely strung out on hard drugs from as much as I could tell. I could not use him. Various guitar players, singers and bass players entered my rehearsal studio at Mercury’s offices where I held the auditions, but no one knew what I was talking about. The Moody Blues? No interest. They were excited about the Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin.

Meanwhile, Blue Cheer, the world’s first heavy metal band, was rehearsing loudly in the studio next door. They were also produced by my producer, Abe “Voco” Kesh. By this time, only one member, Dickie Peterson, remained of the original band, and he was so strung out on probably every drug known to man that he could barely talk. With all of this going on, it was difficult to make a positive rock album. I managed to write four songs, however, but not having a singer, I sang them myself for the demo that I made for Mercury. One song, called “Dawn II” merged the zither with rock and roll bass and drums, and the words addressed the necessity for transcending the material world to reach a realization of the spiritual.

Meanwhile, I was having difficulties. Having little money, Suzy and I were staying in fleabag hotels in San Francisco’s infamous tenderloin district. And everywhere I turned, it seemed as if the people who once were filled with peace and love were now talking about satanism. I recalled the day when after one of the recording sessions, as I was leaving the control room, Anton LeVey was seated in the waiting room, waiting for his, apparently, pal Voco, my producer.

I wanted to leave California as quickly as possible, and as soon as the demo was finished, we headed for Colorado. Suzy turned to me on our way out of San Francisco and commented that San Francisco was just like a circus: “You pay to get in, but it’s free to get out.” She was referring to the toll that you paid to drive into the city from either the east or north, with free passage on the way out. I had seen the glory days of Haight Asbury turn into crime and hard drugs. The dream was over. I hoped I would never return, but that would turn out not to be the case.

Several weeks later, in Colorado, I heard from Mercury. “You are too far out for us. You are too ahead of your time,” I was told. My thirty-year prediction still stood.

Today (2001)

The Dawn album today has a number of fans, especially in Europe. It can be found from time to time on the Ebay online auction where I have seen prices as high as $250.00 for a single copy. The prediction that I made in 1969 finally came true. It has taken many years for the Dawn album to be recognized.*

Since 1969, the year my album was released by Mercury Records, I have released twelve albums of instrumental music on my own label. Dawn set the pace, demonstrating the discovery that I had made of the duochord and positive and negative music. After Dawn, all the music that I have created has been only positive, from the zither recordings on Celestial Ascent to the pentatonic album Yo Ki, my most recent effort at the time of writing this writing.

Don Robertson. Atlanta, Ga. July 15, 2001

* The Dawn album was re-released on both vinyl and CD by the Akarma label in Italy shortly after I wrote this article

The Dawn Album

Two Songs from Late 1969

Don Robertson recorded at least four songs in Mercury’s San Francisco studio in late 1969 in fulfillment of his contractual obligation to the Mercury record label for a second album to be released in 1970, but the label decided to not release any more of Robertson’s music. These two videos were made by Don Robertson using two of the songs as the soundtrack. Don Robertson’s goal in creating these songs in 1969 was to create a popular or rock version of his celestial new age music.

The "Lost Dawn Tapes"

In 2011, Don Robertson discovered a reel-to-reel tape made during rehearsals of music for the Dawn Album in San Francisco during early 1969. He released “Revelation 1” on his website. Here is an article from someone who found it there: Don Robertson’s Lost 1969 Tapes