Minimalism and the Return to Tonality

From the online book: Music Through the Centuries by Don Robertson (2005)

Published on DoveSong.com – Revised and expanded in 2016

Chapter Six – The 20th Century: “Dissolution”

From across the sea came the inspiration that reawakened tonality in contemporary classical music

Two Divergent Worlds of Music

There was an onslaught of discordant classical music that occurred during the first part of the twentieth century. Then, a return to concordant music in our classical music halls began slowly and gradually during the late 1960s. The profound effect that the classical music of North India had upon the classical music of the Western world, especially in America during the 1960s, cannot be overestimated in this return to tonality.

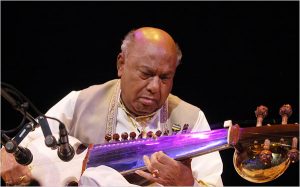

In 1967 and 1968, I was studying contemporary, discordant classical music privately with American composer Morton Feldman, a one-time associate of the radical composer John Cage. At the same time, I was also studying North Indian classical music with the great maestro from India, Ustad Ali Akbar Khan. I was faced with two contrasting styles, one sublimely spiritual, ancient and transcendent, the other cold, frightening, and modern. It didn’t take me long to realize the dichotomy between these two completely opposite styles.

At that time, I discovered the ultimate discord that I named the duochord. This discovery is fully covered in my book “The Scale.” (here)

After I made this discovery, I permanently left the world of discordant “contemporary classical music” with its stressful, negative harmonies. I realized that my discovery was an important one. The next big step in classical music was a shift back to music’s true roots in harmonic tonality. The last big change in style had taken place during the first decade of the 20th century, when Austrian composer Arnold Schönberg began introducing his extremely discordant classical music.

A Change of Style Begins

In 1967, a friend gave me the score to La Monte Young’s 1958 composition Trio for Strings. It had a transparent cover with a translucent photo of La Monte in a thick fur coat. This music is now considered the benchmark piece representing the minimalist music movement and a historic moment in the development of classical music. It incorporated long silences and extended sounds without melodic or rhythmic development. Inspired by looking at a score of Young’s trio and by the music of my teacher Morton Feldman and his friend, composer Christian Wolfe, I began ardently pursuing my own brand of minimalism (although that term would be unfamiliar to me for at least fifteen more years).

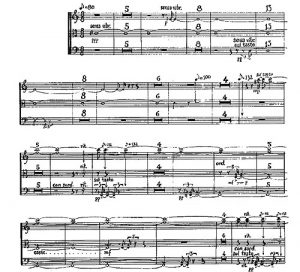

I owned a record containing a piece of music for violin and piano composed by Christian Wolfe. This music consisted of incredibly long silences and very isolated notes. When I slowed that LP down to half speed, 16 RPM, and listened to that, I discovered the kind of empty, stripped-down music that I wanted to compose myself, based on my discovery of the duochord. Soon after, I wrote a musical composition that I called MU for Horn and Piano. It was performed in the concert hall at the Juilliard School of Music in New York City, where I was studying, in 1967. A friend and fellow student performed the horn part on his clarinet.

The sparcity of this music was intense. Very few notes were played by the clarinet and by the piano during the performance, and thus there was a lot of silence. During this Juilliard performance, some of the students in the audience broke out in spontaneous laughter during the first really long period of silence. After about ten seconds, I noticed, people didn’t know how to respond. “Is the piece over?” “Should I clap,” they wondered… hence the outburst of laughter. It was wonderful. The audience had been taken completely off guard, not knowing if the piece had ended or not, and was confronted with nothing on which to place their attention.

What fascinated me about the music was that because of the abundance of space and the sparsity of notes, you could focus on the sounds themselves. The clarinet player told me afterwords that my MU piece had changed his whole appreciation for music, allowing him to understand the actual notes that he was playing as opposed to simply playing music from a score in a mechanical fashion. This was so often the case in so many performances at Juilliard. I was very surprised by that response… but I understood it.

My Juilliard music composition teacher Stanley Wolfe, who was very conservative, was dismayed by my MU composition. He told me that it was way too long (nine minutes) and complained about its unique form and the emptiness of the music. However, I was told by a fellow student that after the concert, he took the score to his advanced composition class to show to the students there.

La Monte Young

Back to La Monte Young. I have never met him personally, but it appears to me that he must be my music-exploration elder brother.

La Monte was born seven years before me in a two-room cabin in Bern, Idaho in 1935. He began his music study at age 7 when his father, a sheep herder, bought him a saxophone. The family moved to Los Angeles where La Monte enrolled in high school. It was there that he discovered jazz, performing it on his saxophone, and it was there that he fell in love with the music of the great master of jazz music, Charlie Parker.

on the cover of "Trio for Strings"

In Los Angeles he began studying with Leonard Stein, Arnold Schönberg’s main American disciple who later became the director of the Arnold Schönberg Institute at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) and curator of Schönberg’s extensive archive. I too studied with Leonard Stein, but it was almost ten years later. In 1957 La Monte was accepted at UCLA. While he was there, the Institute of Ethnomusicology, a division in the university for world music studies, was created, and Young was fortunately able to attend. Like La Monte, I will also benefit by classes at the Institute of Ethnomusicology, but that was nine-years later, in 1966.

Like myself, La Monte’s turning point in his musical life was when he bought a recording of the music of the great Indian maestro, Ustad Ali Akbar Khan. Like me, a few years later, he played it so much that he practically wore the record out. His disgruntled mother even wrote “opium music” on the album cover! Meanwhile, La Monte studied Gregorian chant and medieval music at UCLA and began to draw connections between that music and the music of India, just as I will also do later, beginning with my Gregorian chant studies in 1971, soon followed by studies in medieval and Renaissance-Era music.

When he graduated from UCLA in 1958, Young was obsessed with the music of Anton Webern, medieval music, and with non-Western music, just as I would be in 1966. La Monte Young, whom I have never met, and whose music I had never heard, was foreshadowing my own musical course in so many ways, but I knew nothing of his history until I first wrote this article in 2005.

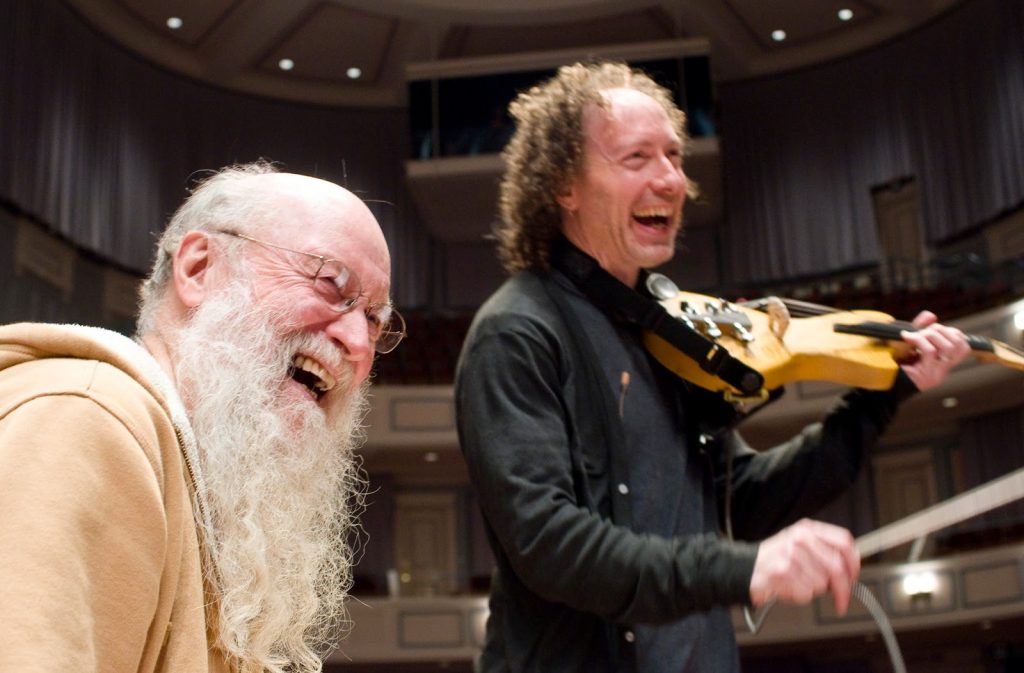

After graduation, Young composed his Trio for Strings that I mentioned above. A performance of this work attracted composer Terry Riley, and they soon became lasting friends.

In 1985, the Los Angeles Herald Examiner called La Monte Young the most influential U.S. composer of the last quarter century, and he is always credited with the birth of the so-called minimalist movement, an unfortunate categorization that limits the scope of the new music trends that began mid-century and that almost completely underestimates the influence of the great tradition of North Indian classical music that I like to call “The Hero From Across the Sea.” The influence of North Indian classical music was responsible for the return to tonality by a few progressive composers and musicians of the time.

In 1959, Young traveled to Darmstadt, Germany. At that time, it was the world-renowned center for “Contemporary” discordant music. There, he was introduced to the music and philosophy of composer John Cage by Karlheinz Stockhausen, the musical leader of the avant-garde in Europe. Young liked Cage’s idea that any sound could be considered music, not just musical notes.

Back at Berkeley, La Monte began organizing noon concerts, and with the help of Terry Riley, he shocked the teachers and students at the university. His composition Vision of 1959 was performed in the dark and created a panic in the audience who were unfamiliar with its strange sounds. Poem for Tables, Chairs, Benches, Etc. of 1960 involved the sounds of furniture being dragged across the floor. I had no idea La Monte had created a piece of music like this when I performed Music for Drawers (being pushing in and pulled out of a cabinet) for friends in my New York City front room seven years later.

In 1960, afraid he would take over the music department with his, and fellow-student Terry Riley’s, shenanigans, the University gave him a travel fellowship. La Monte then went to New York City. By this time, he was writing little pieces that were simply a sentence or two scribbled on a piece of paper that stated such instructions as “Draw a straight line and follow it,” or “play an open fifth” with instructions to play it for a long time.

Soon La Monte Young drew the attention of Yoko Ono. In her large loft on Chambers Street, he began organizing a group of like-minded composers, painters, and writers. Thus “Performance Art” was born. Around 1961, Young became dissatisfied with Ono and performance art, and he drifted away from the scene. Inspired by the “My Favorite Things” and other new albums by John Coltrane (as I also did that same year – even watching him play live in New York City), he decided to pick up the saxophone again. Coltrane, influenced by Indian classical musician Ravi Shankar, was playing florid solos over sustained chords.

La Monte married Marian Zazeela in 1963, and soon they organized an ensemble to back up La Monte’s saxophone solos with a fabric of sustained chords. One member of the group was John Cale who would stay with the group for two years and then leave to organize the rock group called Velvet Underground.

Soon, Young abandoned the sax, but the group continued to perform the long sustained sounds without a melodic instrument. They also abandoned the well-tempered system of tuning that was required for traditional classical music’s many key changes, and instead tuned their instruments instead with what is known as just intonation.

In 1964, Young began work on a work that he called The Well Tuned Piano to be performed in just intonation. This was a composition that could take up to six hours for him to play.

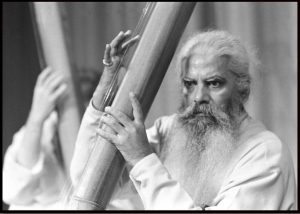

Pandit Pran Nath

During 1970, La Monte and his wife helped bring an Indian classical singer named Pandit Pran Nath to New York City from India. His arrival had been announced a year earlier by a man named Shyam Bhatnagar, who sold copies of a 10-inch red-vinyl LP record of performances by Pandit Pran Nath, apparently made in someone’s living room in India. Raga Bupali was featured on one side, Raga Komel Re Asawari on the other. Bhatnagar held meetings in his apartment. These were attended by many young people, including myself.

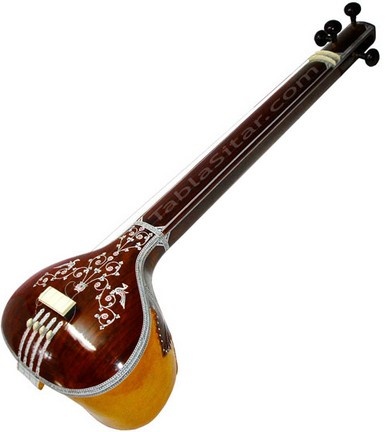

I witnessed things getting out of hand at these meetings, however, when Bhatnagar started placing the gourd of the Indian musical drone instrument called the tamboura directly on the backs of some of the young people who attended his meetings. After long periods performing the three sustained notes of the droning tamboura in this manner, it was obvious to me that Bhatnagar was affecting the sympathetic nervous systems of these young kids in an abusive way. Some of them became so spaced out that they could barely talk or walk for a while after the experience. The famous writer Alan Watts attended one of these meetings and after about forty-five minutes of listening to his dry intellectual explanations of “spirituality” to the fawning youths in attendance, I was so turned off by the whole scene that I quietly left, never to return.

I listened a great deal to the recording of “Raga Komel Re Asawari” on the red record that I had purchased from Bhatnagar, however. The scale of this raga was so very powerful and attractive! But I left New York to study at Ustad Ali Akbar Khan’s new school in California before Pran Nath arrived in New York, and I never returned to live in the Big City again. I would attend classes given by Pran Nath briefly during the early 1980s in California, however.

After Pandit Pran Nath arrived in New York City, Riley and Young both became his students and they will continue to study with him as his two main students for many years. Pran Nath, known to his students as “Guruji,” died in 1996.

As far as La Monte Young’s music goes, I actually had not heard any of it until this week (April, 2016) while editing this article. I have ventured to Youtube to listen to various La Monte Young compositions and improvisations and unfortunately, I have found no music that I am attracted to. In a video excerpt from Well Tuned Piano, I witness the famous mean-tune tuning that La Monte employed, and if this is what he considers “well tuned” then tune me out!

La Monte Young was a forbearer of new musical ideas, but I personally do not hear the results of a fruitful discovery in the various selections of music that I have listened to.

Terry Riley

Composer and musician Terry Riley was born in 1935 and raised in Colfax, California in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. His parents gave him a violin when he was six, but he later switched to piano. Riley attended high school in Redding, California and there he became acquainted with so-called “contemporary” discordant classical music and bebop jazz. He played in the high school band and orchestra, and with a small dance band after school, practicing to become a classical pianist for years. In 1955, when he entered San Francisco State University, did he decide to become a composer. He enrolled at University of California at Berkeley in 1958 and met La Monte Young there.

After Young left for New York, Riley became interested in using repetition as a musical structure. In 1960, he began experimenting with tape loops (music that was recorded on a single piece of mylar recording tape. After the ends of this long piece of tape have been spliced together, the loop of tape is run continuously through a reel-to-reel tape recorder – I watched Bernard Xolotl do this back in 1980. His tape loop was draped across two chairs, I believe).

In Berkeley, Riley began listening to non-western music recordings. Soon he attended a concert by Indian classical music maestro Ravi Shankar. In 1962 and 1964 he traveled to Morocco where he became familiar with the music of that country.

In 1964, Riley visited New York City. He spent time with La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela while he was there. In November he presented a new musical composition called In C that will become the seed from which what later will spring what will be called “minimalism” by the Great Unwashed. The term minimalism, as always, was invented by writers trying to categorize new music trends.

When performing In C, the performance space was completely darkened, and the room was filled with projected light and colored patterns.

Columbia Records’ classical division released In C in 1968 on a 12-inch LP, and it quickly became the anthem for a new kind of music. It wasn’t accepted in the classical-music world, where King Discord ruled the roost, but it had a significant impact on counter-cultural musicians and avant-garde-leaning rock artists.

Riley was apparently seeking a spiritual sound wherein one could loose oneself, giving in to the sounds, much like La Monte was doing, only Riley was using patterns while Young used sustained chords. In C consists of 53 musical ‘clips’ – short melodies or harmonic fragments in C major – and the performers can repeat one of these as often as they wish before moving on to the next. The piece (for any number of players or any kind of instruments) ends when the last player has finished.

Raga Darbari Kanada by the Ali Brothers

Riley moved to New York in 1965. The following year he bought a soprano saxophone. In 1967 he began performing his piece Poppy No-good and the Phantom Band. I attended one of these performances and found the music unstimulating. I had no interest in perusing Riley’s music further. In fact, at that time, I had become completely mesmerized by the great North Indian raga Darbari Kanada, and especially the recording by the Ali Brothers of Pakistan, and nothing Riley played could compare to this exalted performance of the greatest raga in North Indian classical music. Amen.

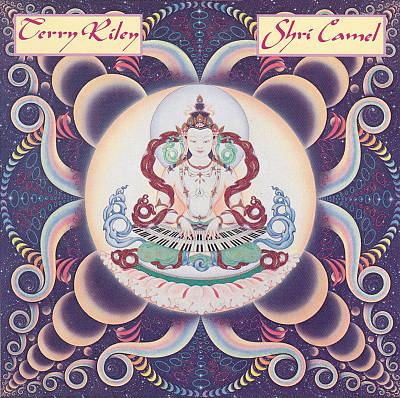

Riley moved back to California, where he has remained to this day. During the 1970s he, like myself, composed no music. Instead he and La Monte Young concentrated on learning North Indian classical music from Pandit Pran Nath. Personally, I have never been attracted to Riley’s music. I don’t find init the same spirituality to be found in the music of the great North Indian classical singers. Riley spent many years at the feet of the singer Pandit Pran Nath, but I don’t hear the influence of the great Indian music tradition in Riley’s music. My friends, Bernard Falconer and Barbara Xolotl, whose painting adorns the cover of Riley’s Shri Camel album, and who consider Riley to be a great musical master, completely disagree with my opinion of Riley’s music.

One would hope Riley would have gained important spiritual knowledge through his studies with Pandit Pran Nath. North Indian classical music is one of the most positive and most important musical traditions in the entire world! Somehow, however, instead of moving forward, Riley has returned to the discords of the twentieth century classical music in the works that he has composed for various commissions. In my opinion, his Solome Dances for Peace, recorded in 1989 by the Kronos Quartet, are less about bringing us peace, and more about a kind of nervous despair, for example.

However, Mr. Riley, according to his website, conducts seminars on North Indian classical music and I commend him for that. This is a most important musical tradition that we, who have seen this light, must now pass on to those in the younger generations who are seeking the true reality of what music can be, and yet who have no idea that such music even exists, let alone the power and greatness of music composed and performed by the great masters who have left behind their knowledge via their students and the imprint of their performances through recordings.

Some of the followers of Pandit Pran Nath, who was teaching Indian music North of San Fransisco in Marin County back in the 1980s, looked askance at the school of Ustad Ali Akbar Khan that I was attending in nearby San Rafael. I was even told that I was studying with the “wrong teacher” by one oft he students during the times that I attended Pran Nath’s classes. Ustad Ali Akbar Khan was an incredibly great musician of the highest order… a master. We, the longtime students of Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, learned a great deal from our lessons with this great musician.

Meanwhile, from one of Ali Akbar Khan’s fellow students, I was told a story of that Pandit Pran Nath did not have a favorable reputation among musicians in India, and that when he was confronted about his teaching American students, Pran Nath said “Please, don’t mess this up for me.”

These are just anticdotes. I only share them because perhaps they may be useful sometime.

Minimalism

Following Terry Riley and La Monte Young, a new trend in music began, begging for a place alongside so-called “contemporary” or “serial” music in the world of ‘hi-brow’ classical music. It acquired the name minimalism, or minimalistic music.

The term had been introduced in the world of visual arts during 1965 and was first applied to music by Barbara Rose in a 1965 article called “ABC Art,” referring to the music of La Monte Young and Morton Feldman. In my opinion, the term applies more directly to the music of these two composers than it does any of the composers that the world has come to associate with the term. Strictly, it refers to using a minimum amount of sound to construct the music, such as we find in Cage’s 4’ 33” and the works of Feldman and Le Monte Young (and don’t forget Christian Wolfe). But the term has come to be applied to the works derived from Riley’s famous In C and the works of composers Phillip Glass and Steve Reich, where repeating musical patterns are employed.

It is perhaps uncertain where the term minimalism actually originated. By 1972, the music of La Monte Young, Philip Glass, Terry Riley, and Steve Reich was sometimes called the music of the hypnotic school and often was referred to as trance music. The term began to be associated specifically with the music of Phillip Glass and Steve Reich in 1972, when it was introduced in print in an article by Tom Johnson that appeared in the Village Voice. After the debut of Steve Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians and the production of Philip Glass’s Einstein on the Beach at the Metropolitan Opera House in 1976, music critics began to look for a label for the new musical style that these composers were using, and the term minimalism started to become the standard descriptive term, although the term trance music will still be widely used for a while. As had occurred when the term impressionism was invented, the main composers to which the term has been applied have never approved of it themselves.

The main composers who have been identified with the minimalist movement are La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, Philip Glass and John Adams. Their influences were John Cage and John Coltrane, the latter who was influenced by Ravi Shankar, and North Indian classical music. All these musicians recognized that the discordant “contemporary classical music” currently holding forth needed to be transcended. In fact, Riley is said to have labeled the music neurotic. They all turned away from serial music, criticizing it. Glass called the European serialists, such as Boulez, Nono, and Castigliono, “creeps.”

While Glass was, perhaps superficially, influenced by Ravi Shankar, the classical singing tradition introduced to Riley and La Monte Young by Pandit Pran Nath was much deeper.

Steve Reich

New York City native Steve Reich was born in 1936. He studied the piano for two or three years as a child but didn’t really discover music until he was 14 when he first heard bebop and classical music. His preference was baroque and 20th century music. In 1953 he entered Cornell University where he played drums with a jazz band after school. In 1957, he began studying composition with Hal Overton. He then entered the Juilliard School of Music. During this period, he discovered the contemporary classical composers Boulez, Stockhausen, and Berio.

He met Phillip Glass at Juilliard, but they did not take to each other. Neither did either of them like La Monte Young’s Trio for Strings. In fact, Reich did not grasp the full significance of Morton Feldman’s music until long after the composer’s death in 1987! This disproves the theory that their music was related to the first real minimalist composers!

Reich dropped out of Juilliard and moved to San Francisco and began studies with Berio at Mills College in 1961. That year, he (along with many other musicians, including La Monte Young and myself) discovered the music of John Coltrane. Reich felt a pull between what John Coltrane was doing and what Luciano Berio was doing, a pull like I had with Feldman and Ali Akbar Khan. Remember, the modal jazz that Coltrane was playing was a direct result of his contact with North Indian classical music.

After Graduating from Mills in 1963, Reich began experimenting with tape loops, as had Riley. He soon met Riley, who showed him the score for In C. Reich liked what he saw and volunteered to help Riley with its performance. He then created a tape piece called It’s Gonna Rain in 1965 using identical tapes of a recorded speech pattern that were out of phase. This piece was inspired by Riley, and when Riley heard it, he was angry, and they apparently have not gotten along since this time. Riley felt that he had been ripped off by Glass and Reich and dedicated a piece to them called The Rite of the Imitators.

Reich moved back to New York City in 1965 and continued making tape pieces. After another piece in 1966, Reich realized he had grown tired of working with tapes and longed to write for real instruments, which he began doing in 1967. The first piece, Piano Phase, used two pianos to create the out-of-phase condition that he had been realizing with tape. He organized an ensemble and in March of that year, presented the piece at the Park Place Gallery, at that time the main gallery in New York City that was displaying minimalist art and sculpture. Phillip Glass came to see what his old schoolmate was doing. Soon, they combined their ensembles to perform both of their compositions.

Reich continued to compose, the combined Glass-Reich ensemble performing his works mainly at art gallery venues. In 1970, he wrote Four Organs, a piece that used four small electric organs to expand a single chord from its inception of a single pulse. In October 1971, Four Organs was presented in Boston’s Symphony Hall, included in a program of music by Mozart, Bartok, and Liszt. In January 1973, the conductor who presented Four Organs in Boston arranged for a performance in Carnegie Hall where a near riot broke out. Next Reich studied African drumming and then composed a piece called Drumming for percussion instruments and voices. In four parts, the first part is for four pairs of tuned bongos, the second for three marimbas, the third for three glockenspiels and piccolo, and the fourth for all the instruments together.

Reich soon became recognized as a composer. With his ensemble now separated from Glass’s, he began touring in 1971. At that time, he began studying the Indonesian gamelan. He wrote Music for Mallet Instruments in 1973, then after nearly two years of work, he created Music for 18 Musicians, a piece that garnered wide acceptance. He started receiving commissions, mostly from Europe. More works were the result of commissions that he had received.

Philip Glass

Philip Glass was born in 1937 in Baltimore, Maryland, the grandson of Jewish immigrants from Lithuania and Russia. His father sold records, and this enabled Philip to listen to a wide range of music when he was a child, both classical and popular. He began studying violin at the age of six, then switched to flute and finally to piano. He was admitted to the University of Chicago in 1952 when he was only fifteen years old. He majored in mathematics and philosophy and listened to the music of “contemporary” discordant composers Anton Webern and Charles Ives during his spare time. He graduated at age 19. By then he had begun composing music. His early work was in the style of Anton Webern.

Glass entered Juilliard School of Music where he abandoned the style of Webern and began writing in the style of Aaron Copland and William Schuman who were the predilection of Juilliard school during the 1950s and 1960s. He received his master’s degree from Juilliard in 1961. He wrote very conventional music for a living for a while, until he decided to return to Paris in 1964, ten years after his first visit there. There, he studied with the famed teacher Nadia Boulanger who had taught Copland and Virgil Thompson.

During his second year with Boulanger in 1965, he was hired by Conrad Rooks to be the musical director for his move Chappaqua. One of his duties was to transcribe into Western notation the music of Ravi Shankar that was to appear in the film. Glass spent several months with Shankar and Alla Rakha. It was during this period that Glass discovered what he needed to begin a new musical journey.

Similar to what John Coltrane learned from Ravi Shankar, Philip Glass really learned very little. This is not meant as a criticism; Glass has never claimed any differently, nor had Coltrane. Composers in the past have tried to use what they have learned from Middle Eastern and Indian music to influence their own style without spending much time really absorbing it. Opportunities for serious studies were not available until the late 1960s. Composers such as Terry Riley and La Monte Young are examples of those who took the challenge of really absorbing what other great music traditions had to offer.

Glass had never heard Indian music before. What Glass thought that he had learned from Ravi Shankar and tabla player Alla Rakha was that their music was not cyclic as was ours but was a continuous flow of beats that was constructed in an additive process. This understanding, although not correct, gave him the ideas that he would use for his own music. He had completely misunderstood the music, but it inspired him, nonetheless. This misunderstanding, he recognized and acknowledged later. But just the same, Ravi Shankar and Alla Rakha stimulated him to start in a new direction.

Back in New York, in March 1967 Glass attended a performance of Steve Reich’s music at the park Place Gallery, and as explained above, the two began working together. That year Glass composed Strung Out for solo amplified violin, a piece that consisted of a steady stream of rapid eight notes and no bar lines, and used only five pitches, the repetition proceeding by means of the additive process he thought he had acquired from Ravi Shankar. Two Pages for Steve Reich of 1968 consisted of a single line of music played on electronic keyboards and wind instruments. The line of music is expanded and shortened in the process of development. The additive process works by adding or subtracting notes in a repeated phrase. Music in Fifths has two lines of quickly executed eighth notes, each line expanding and contracting. Both go along side by side as parallel faiths. Music in Contrary Motion had two lines of eighth notes moving in contrary motion, with a bass provided as a drone. Music in Similar Motion began with one line of unison eighth notes that expanded to four lines, all moving similarly. All these obviously experimental works, stark and stripped-down, were composed during 1969. In the following year, Glass composed Music with Changing Parts, another experimental work.

As is the case at any of the times where artistic styles make a radical change, the performances of the Philip Glass Ensemble caused a controversy. In Amsterdam, a man from the audience ran onto the stage and tried to play along with Glass, who punched him, knocking him off the stage. In 1972, the director of the Spoleto Festival in Italy, opera composer Gian Carlo Menotti, walked out on the festival during a Glass performance, and someone tried to cut the power supply. In New York in 1973 a man screamed “They’re not musicians! They can’t play! I’m a music teacher and I know they’re not really playing their instruments!”

In June 1974, Glass made his first appearance in a downtown New York concert hall, Town Hall, and received a standing ovation. He performed Music in Twelve Parts, a piece that he had been working on since 1971. Glass also began meeting with the visionary American stage director Robert Wilson and work began on Einstein of the Beach, his first opera, based on the character of Albert Einstein. Nearly five hours long, the Philip Glass Ensemble supplied the music. Einstein on the Beach has no character development or conventional narrative, and there is no story or plot. It had its world première in August 1976 at the Avignon Festival in France. After playing in five other European countries, Glass brought it to New York, and in November he sponsored a performance at the Metropolitan Opera on a night when the hall was available for rental. He believed enough in it to fork out the money for the performance. Word of the opera had apparently reached New York as the performance was sold out. It cost Glass $900,000 for Einstein’s productions that year. The work was a huge success, but Glass returned to driving a cab.

His next opera was Satyagraha in 1979, then Akhnaten in 1983. After these three operas, Glass became the most familiar and the most requested living composer.

John Adams

The laurel of most-performed living composer was passed to John Adams in the 1990s. Born in 1947, he is younger than the other ‘minimalist’ composers.

As a teenager, he played clarinet in a New Hampshire community orchestra, the only teenager in the otherwise adult orchestra. He conducted his first large-scale composition when he was thirteen, attended Harvard University and in 1967 became a hippie. He wrote a setting for chamber orchestra and soprano of a song cycle based on psychedelic poems written by a friend at Harvard. After he entered Harvard, he began to realize that he was living a double life. In class, he analyzed tone rows in Anton Webern’s music, but outside of class he got high and listened to the Rolling Stones and John Coltrane. His spiritual side was in this music, and his musical studies in discordant contemporary music was a lifeless drill.

He received a master’s degree from Harvard in 1971. As a graduation present, his parents gave him Cage’s book Silence, and this book transformed his world completely. He moved to San Francisco after graduation, taking the book with him. From 1972 to 1982, he worked at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music where he was the head of the new music program. He played with sound for a while, then electronic instruments, but after five years of electronic collages and Cage-like creations, he turned to tonality. In 1974, he Heard Steve Reich and that converted him to “minimalism,” but he took a more emotional direction. “I’m trying to embrace the tragic aspects of life in my work.” he said in 1985. Also, in 1992, he said “I think minimalism was a wonderful shock to Western art music.” He also states that what makes him different from Glass and Reich is that he is not a modernist. He embraces his past, rock and roll and all.

His first minimalist pieces were the piano piece Phrygian Gates (1977-1978) and string septet Shaker Loops (1978).

Adams returned to tonality out of the morass of discords in the classical music of his time, but later he abandoned tonality, brought in the discords, and incorporated chaos and insanity into his music, for example in the orchestral work Naive and Sentimental Music of 1999 and the Violin Concerto of 1993.

The Rebirth of Tonality

The new “minimalist” composers met their challenge in 1984 when the infamous Darmstadt controversy occurred. Darmstadt, Germany was the bastion of “contemporary” discordant music during the second half of the twentieth century. The European “serialist” movement originated there after World War II. Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen had both emerged from Darmstadt and all the major European composers, Boulez, Stockhausen, Berio, Nono, etc, came there for concerts and study, and the Darmstadt Orchestra was performing discordant works continually. There had been a standing joke among musicians that the members of the Darmstadt Orchestra were all sterile (because of the music).

Darmstadt stood for the pinnacle of new Western classical music and was known the world over. However, a shock came to the Darmstadt community in 1984 when the International Summer Course for New Music in Germany (as it the yearly festival of new music that took place at Darmstadt each summer was called) included for the first time, works by the minimalists!

This was a full twenty years after Terry Riley’s In C had been composed. The discord community felt nothing but scorn and condescension for composers who wrote tonal music, and allowing them into this select circle? Well, that was the ultimate disgrace! But it had been felt by some at Darmstadt, including the recently designated director Friedrich Hommel, that the summer festival should no longer be the exclusive domain of the atonalists and serialists. That summer, major works by such composers as Terry Riley and Philip Glass were perfumed along with European works that were written in a romantic style. This caused explosive reactions!

This event marked a point in history. The old would have to give away to the new. Now in a steady decline, the reign of discordant music would diminish, although even the minimalist composers had not themselves completely abandoned elements of stress and discord in their own music! But the event was a milestone in the return to tonality.

Some composers have embraced tonality, some not completely, some, like Easley Blackwood, who shocked critics with his romantic 5th Symphony, making a complete turn around. Henryk Górecki’s tonal Third Symphony made it into the pop charts in England!

The return to tonality will not be complete until the 21st Century, however.